The lone dwelling standing oddly intact, unblemished even, amidst the charred remnants of a collective past having been suddenly and violently erased by fire—it is an image that is rapidly becoming normalized. Los Angeles’s Palisades and Eaton fires earlier this month, with their structure losses totaling 6,380 and 9,418, respectively, and a combined damage and economic loss estimated at $250 billion, have provided our most recent examples of such unlikely “survivors.” That a few buildings, the houses especially, managed to withstand the conflagrations that consumed everything around them have made them the subject of widespread fascination: Why did these houses survive, and why not their neighbors?

And as new fires continue to erupt around the city, other questions become unavoidable: Why haven’t all houses been built like those—and what would it cost to have one built?

Follow THE FUTURE on LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, X and Telegram

A Nation of Tinderboxes

They are simple questions with complex answers. But while the question of cost varies wildly by design, location and a myriad of factors, the answer is not always significantly more: A study by the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) found installing additional wildfire safety measures, beyond the state’s current codes, added only 2 to 13 percent to construction costs—and that adding “optimum” wildfire building materials like metal roofs cost $18,180 to $27,080 more. Meanwhile, the National Bureau of Economic Research found that homes that met wildfire codes are 40 percent less likely to be destroyed in a fire than other homes.

Indeed, the brutal reality is this: In today’s extreme-climate era, in the event of wildfire, a house designed and built for any preceding era stands little chance of survival. To understand this, the Los Angeles neighborhood of Pacific Palisades, tragically, is highly instructive.

Pacific Palisades’ housing stock, much of it of the tract type, dates primarily to the 1930s and ’40s. While at that time the Uniform Building Code, the City of Los Angeles’s standard, included in its provisions a “fire-resistive” category—buildings defined principally by their structural frames of either steel, iron or steel-reinforced concrete—the city’s prevailing aesthetic preferences resulted in few of its residences being built as such. Instead, the L.A. homebuilding industry, like that of most of the United States, was reliant mainly on the wood-frame dwelling, a method of construction that had long proliferated under a comparatively permissive code. It was a code that, from a fire-vulnerability perspective, allowed for a dangerous, relatively omnipresent building-envelope porousness.

In these decades before the introduction of integrated mechanical cooling in the single-family home, houses were decidedly low-tech, expected to be capable of “breathing” on their own. (In Los Angeles, air conditioning didn’t arrive until the 1950s, and widespread adoption would come a decade or two later.) Unsealed doors and poorly insulated, often double-hung single-pane windows were common. During the warm months of the long Southern California dry season, houses relied on a haphazard approach to passive cooling. In the site planning of the tracts, orientation to prevailing winds was typically left to chance. Meanwhile, roof and subfloor spaces were thoroughly vented, usually without screens, to allow for some measure of natural cooling.

Those vents also carried one self-destructive flaw: they admitted burning embers into a home. And from there, the dangers compounded: The common approach to eave design created areas of the roof that practically invited and would trap flying embers. Combustible materials in exterior cladding, such as timber weatherboarding and wood shakes and shingles, were widely used. The period’s stucco product, the common alternative to wood for exteriors, was inferior to today’s, carrying only a one-hour fire rating. Roofs were often given the then-popular “rustic” treatment, surfaced with either easily ignited wood shakes or shingles. And all of these dangers were multiplied by proximity to one’s neighbors: Common side-yard setbacks were little more than half of what they are today.

The result—not just in the Palisades, but throughout the nation, as the homebuilding contractions of the Great Depression were followed by the post-World War II housing boom’s fast-tracked and cost-cutting practices—was a legacy of fire-prone houses. Great ignition vulnerability was practically “built in.”

The Cost of Change

“Changing industrial conditions have brought reinforced concrete construction within the reach of the average home-maker,” wrote Frank Lloyd Wright. “A structure of this type is more enduring than if carved intact from solid stone, for it is not only a masonry monolith but interlaced with steel fibers as well.” The year was 1907, and Wright was promoting his latest invention, “A Fireproof House for $5,000.”

Three decades after Wright’s well-publicized offering, homes of reinforced concrete construction—not only in Los Angeles of the 1930s and 40s, but nationwide—have remained for consumers a near-impossible sell. But why? In short: We like what we like, and cost is a main concern.

Then as now, the ways in which we choose to house ourselves are rooted in notions of American individualism—and in ideologies marked by personal allegiances to domestic rituals and aesthetic predispositions. In matters of design, materials and construction we gravitate straight to the familiar: wood-frame construction, dressed up in the day’s recognizable fashions.

It’s perhaps only now, given the increasing cadence of destructive wildfires, that marketplace acceptance of the aesthetics of a function-first, fire-resistant kind of house is even possible. For the roughly 44 million Americans who live in what the U.S. Fire Administration refers to as the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI), the “zone of transition between unoccupied land and human development,” that need is urgent. Those areas are ubiquitous and growing, encompassing, according to FEMA, some 190 million acres: California, Texas, Florida, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania are the states with the most houses in the WUI. Close behind them are those in the ever-expanding non-WUI areas of the nation that are increasingly prone to wildfire. But for homeowners in those areas motivated to build such a house, what exactly does one look like…and what are the differences in cost?

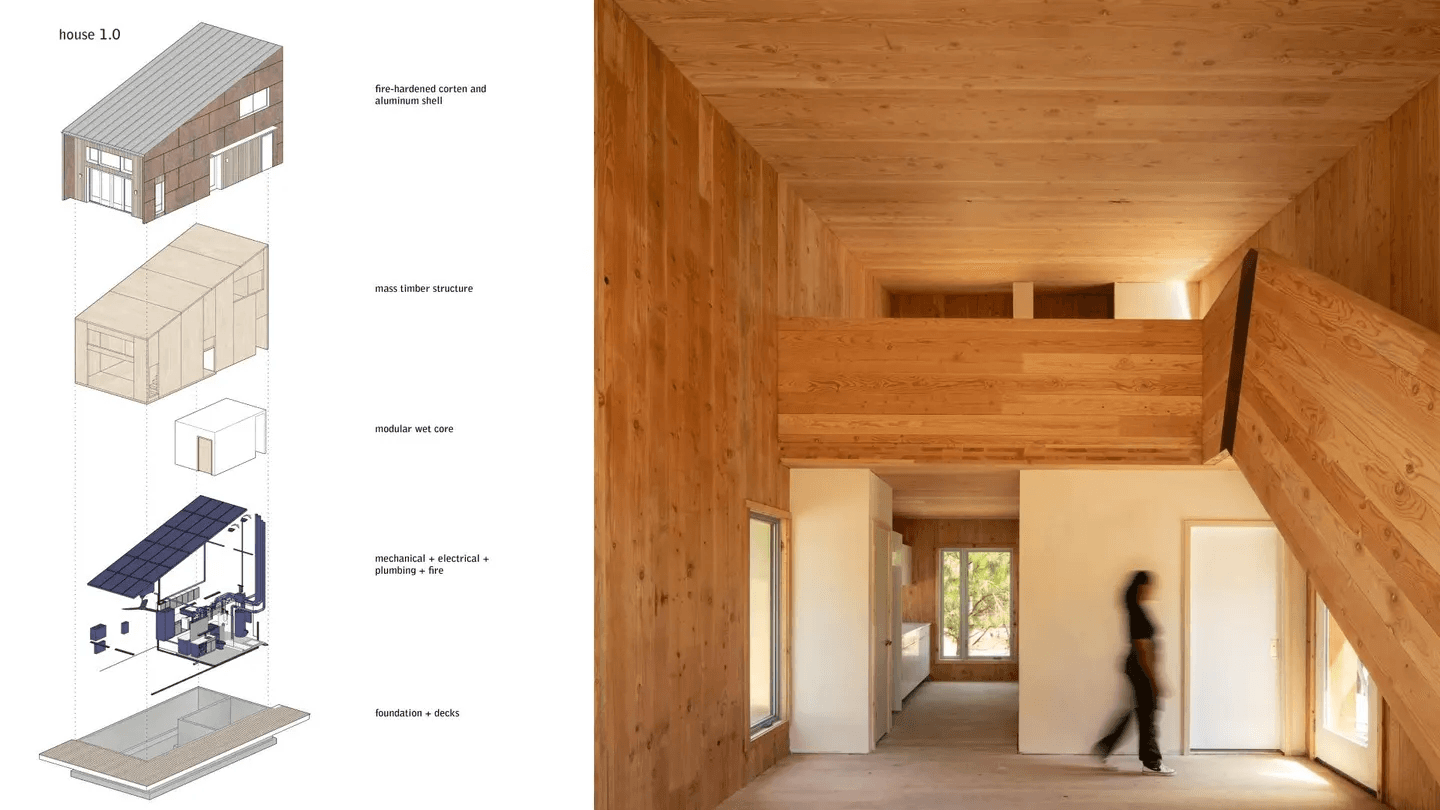

Left: atelierjones; Right: Lara Swimmer

Lara Swimmer

Seattle-based architect Susan Jones, principal of atelierjones, has worked on the front lines of that question for years. Following the 2021 Dixie Fire, which destroyed the town of Greenville, California, leveling nearly 700 houses, Jones’s firm stepped in with rebuilding solutions attuned to local factors. Her approach, which she characterizes as fire-hardened, or fire-resistant (“not fire-proof,” she cautions), involves a specific palette of materials and systems of construction. Inevitably, her houses have metal roofs, a prefabricated “wet core” and a carbon-reduced, fire-hardened mass-timber shell. Insulation, usually mineral wool, is continuous in application. For air tightness, as part of her handling of detailing toward the “Passivhaus” standard, she employs a strategy designed “to give the house a positive pressure, via a heat recovery ventilator, to push the smoke out.” And on average, for atelierjones’s houses, the additional costs of construction tend toward 5 to 10 percent of the total.

Bruce Damonte

Another architect who’s worked extensively in fire-resistant design, specifically in cross-laminated timber (CLT) construction and in concrete, is Casper Mork-Ulnes, whose 20-year-old eponymous firm has offices in San Francisco and Oslo, Norway. “There’s different layers of fire resistance, depending on how secure you want to be with your home,” says Mork-Ulnes. “I believe that keeping things simple is clearly the best way to create a fire-resistant house, and that is by creating defensible space and by using non-combustible materials, having simple roofs, and just being more elemental in the design of the project.” He, himself, cites approximately 10-20 percent as the added costs of his fire-resistant house, but adds that the costs can fluctuate on the basis of the type of concrete used.

“The big challenge is that people love wood,” the architect adds. (Indeed, some 94 percent of new home completions in 2022 were wood-framed.) “It has a certain tactility, the olfactory qualities of it, the ageing of the wood. That’s the biggest hurdle to get through with clients. I think people, culturally, in the United States, with metal and concrete, there’s a cultural disposition against that material as a residential material. I think it’s mostly thought of as a commercial and industrial material and that it’s cheap. That’s something that’s not true.”

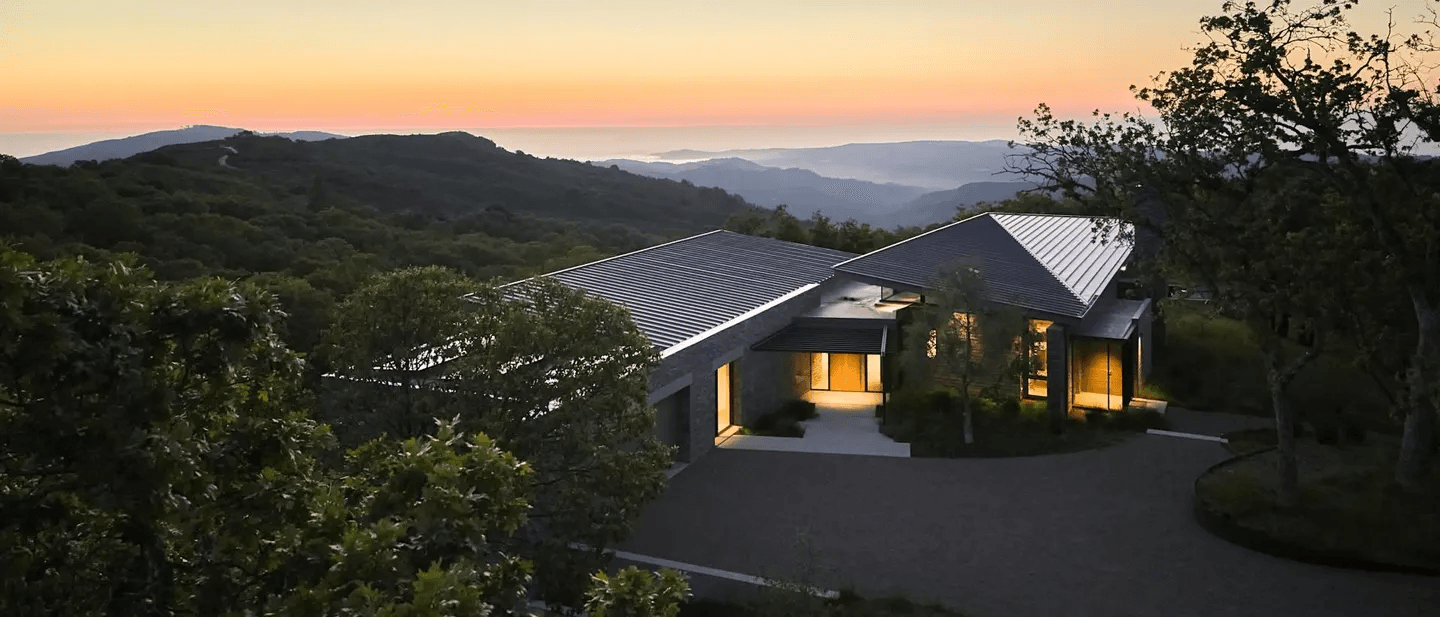

Matthew Millman, Jonathan Mitchell

Architect Gregory Mottola, a principal at Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, a firm founded in 1965 and with offices in Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Wilkes-Barre, San Francisco, and Seattle, has wide experience with fire-resistant design. And Mottola is not alone in believing that it will ultimately be market forces—specifically the insurance industry—that compel its more universal adoption.

“These days,” says Mottola, “one of the first things we talk about with clients is really limiting, or eliminating, combustible materials on any exterior surface. We’re doing a lot more concrete, and stone, and metal. In a house we designed for Carmel, California’s Santa Lucia Preserve, for example, we do have some areas where we have cedar, but that cedar is backed up by a product specifically designed for these kinds of environments, where wildfire is a huge risk. The envelope is a bit more expensive, because you’re doing rated assemblies on the exterior.

“Maybe the biggest deal,” Mottola says, “is that the fire insurance companies that are either writing the policies—or, as the case may be, not writing the policies—are becoming much more vocal about demanding that certain kinds of measures be taken, very often going above and beyond what the code requires.”

And therein lies the ultimate rub: the money. In the end, for a client to build this way, they must recognize the far greater lasting value that comes with a fire-resistant building. And California, in this regard, is again a cautionary example. In March 2024, State Farm, the region’s biggest insurer, announced it was canceling 72,000 policies in California in certain high-risk areas; the company canceled 1,600 policies in the Palisades alone in July of last year. According to the California Department of Insurance, insurers canceled 2.8 million homeowner policies in the state between 2020 and 2022.

As Mottola says of his clients today: “I think they all see it, that they’re going to build a more robust home because they’re building in a risky place. Building a home that you can’t get insurance for is a horrible outcome, too. Between the insurance companies and the code, we’re all being pushed there.”