Loneliness has become Europe’s silent epidemic. The 2022 EU Loneliness Survey reveals that 13% of Europeans feel lonely most or all of the time, with 35% experiencing loneliness regularly.

Despite stepping into an era of unprecedented digital connectivity, genuine human connection appears to be deteriorating. Loneliness is not simply being alone. Research from Verywell Mind (2023) describes loneliness as “a state of mind” where individuals feel empty, alone, and unwanted, even in the company of others. This definition emphasizes that loneliness is not solely about the physical aspects that comprise isolation, but rather about the perceived disconnection, which often makes it harder to form connections and, consequently, creates a feedback loop between perception and further disconnection.

Follow THE FUTURE on LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, X and Telegram

And the consequences are not just social. A 2015 meta-analysis by Holt-Lunstad et al., reviewing 148 studies with over 308,000 participants, found that social isolation increases mortality risk by 29%, while loneliness increases it by 26%. These health risks are comparable to smoking or obesity. The U.S. Surgeon General’s 2023 advisory echoes these findings, stating, “Lacking social connection can increase the risk for premature death as much as smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day.” Researchers have also connected the physiological toll of loneliness to disrupted sleep, elevated cortisol levels, increased blood pressure, and higher rates of cardiovascular disease.

A 2023 policy brief from the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre classifies loneliness as a serious public health concern, one with far-reaching emotional, social, and physiological effects. The report states, “social connections are fundamental for individual well-being,” and EU institutions are beginning to treat prolonged loneliness not just as a personal issue, but as a systemic one, using cross-national data to inform social and health policy across the bloc.

While governments are only beginning to explore long-term policy responses, some in the tech world are already moving fast. Alex Kudos, CEO of SDG Lab Venture Studio, which is backed by Social Discovery Group, doesn’t just view loneliness as a crisis; he sees it as a cultural moment that is demanding new (or redefined) models of connection.

“Technology isn’t just helping us form relationships — it’s becoming a part of them,”

he says.

Through a $20 million corporate venture studio backed by Social Discovery Group, SDG Labs is funding startups focused on “virtual intimacy,” which he defines as “emotional closeness, connection, and bonds that users can develop and share through digital platforms.”

It’s a vision that challenges conventional assumptions about human connection. But it raises an uncomfortable question: if loneliness stems from a lack of emotional intimacy and genuine understanding rather than mere social contact, can virtual relationships truly provide the depth needed to combat isolation, or do they simply offer a more sophisticated form of surface-level interaction?

The Geography of Loneliness

The loneliness crisis isn’t distributed equally across Europe. The same 2022 EU Loneliness Survey reveals noticeable geographic differences: countries in Eastern and Southern Europe, such as Bulgaria, Greece, and Romania, report significantly higher rates of loneliness compared to Western and Northern nations such as the Netherlands and Austria. These differences suggest that economic factors, aging populations, changing social norms, and weakened public infrastructure all play a role in determining who feels most isolated. And why.

Cyprus, where Kudos has established his base, is no exception to the Southern European trend. The island nation reports some of the highest rates of loneliness among older adults in the EU, a demographic challenge that resonates with the SDGs’ current focus. “We see virtual intimacy as a powerful tool in addressing loneliness, especially among older populations,” explains Kudos. “We’re keen to explore and pilot solutions that use technology to build meaningful connections.” Living locally, he adds, has deepened his understanding of the island’s social needs and has informed the development of more context-sensitive technology solutions.

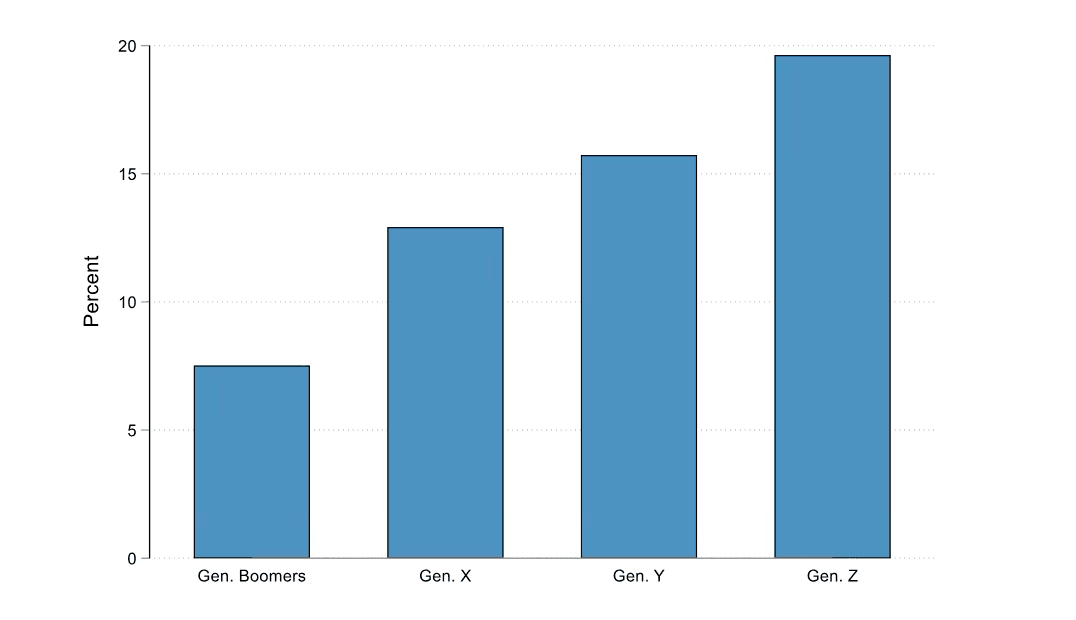

This focus on digital companionship for older users is part of a broader evolution in how people connect across all age groups. Kudos, in our interview, mentions research showing that 57% of Gen Z consider online relationships as meaningful as in-person ones. “They don’t hold the same outdated notions,” he argues. “Technology is already part of how they form and feel connection.” We saw this quite clearly during the COVID-19 pandemic, which only accelerated what researchers call the “normalization” of virtual-first relationships.

During lockdowns, millions discovered they could maintain emotional connections through screens, signaling a cultural shift in expectations about what constitutes meaningful interaction. Indeed, research from AltspaceVR during the pandemic found that participants reported lower loneliness and social anxiety in virtual reality environments compared to the real world, attributed to immersive social interactions like meeting friends and attending events.

But it may be too soon to jump head-first on the screen-only train. While some studies have revealed that some users embrace digital connection as genuinely meaningful, others experienced what researchers describe as “telepresence fatigue”—the sense that virtual interactions, while better than nothing, remained fundamentally inferior to physical co-presence. This tension between digital convenience and authentic intimacy and depth forms the backdrop against which companies like SDG are developing their solutions.

The stakes extend beyond individual well-being. As Béatrice d’Hombres from the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre has pointed out, loneliness creates measurable economic costs, from increased healthcare usage to lower productivity, and the growing pressure on social services. For countries like Cyprus with aging populations and limited in-person support networks, the economic argument for tech interventions becomes increasingly compelling.

Beyond Dating Apps: The SDG and SDG Labs Portfolios

Social Discovery Group is one of the world’s largest social discovery companies, operating over 60 brands with 500 million registered users across 150 countries. The company launched Dating.com in 1998 and has since expanded through acquisitions, including CupidMedia and DilMil.

The portfolio targets specific demographics: DateMyAge for singles over 45, DilMil for South Asian communities, and Kiseki for Japan’s digital romance market. According to Alex Kudos, this segmentation reflects how “globalization has a significant role in the rise of loneliness, as people move away from where they grew up, their communities, and their cultural norms.” These platforms, he explains, are designed to support people navigating unfamiliar cultural environments, helping users who may be geographically distant from their roots to still find a sense of belonging through shared connection.

SDG Labs Venture Studio, which was recently launched, takes a different approach from traditional venture capital. Instead of what Kudos calls the “spray and pray” model of most investment firms, SDG carefully picks and builds 5-10 ventures annually, offering each full operational support. Current investments include Joi AI for AI character relationships, a virtual influencers platform, and AI products for seniors, plus two Cyprus-based startups.

The Critical Questions

Before we accept virtual intimacy as the cure for our loneliness, or shall I say, disconnection crisis, we need to confront some uncomfortable truths. The research paints a complicated picture, one that challenges a somewhat simplistic, surface narrative around technology engineering its way out of a crisis.

The Bandage vs. Cure Dilemma

Consider the paradox discussed earlier in regards to the research around AltspaceVR. Though the technology showed promise in reducing loneliness during COVID-19 lockdowns, participants consistently reported that these virtual interactions felt inferior to in-person connections. The technology provided relief, but was it healing or simply numbing the pain?

This tension reflects wider findings around digital connections. A UK-based study on telepresence technologies found that while video calls helped maintain long-distance relationships, they were often perceived as “inferior to in-person contact” and lacked the warmth and nuance required to form new (and sustainable) bonds. As one researcher put it, we may be offering digital prosthetics for emotional loss, but that doesn’t mean they function like the real thing.

The Accessibility Trap

The EU loneliness data reveals another troubling pattern: loneliness disproportionately affects lower-income and less-educated populations, the same groups with the least access to cutting-edge virtual intimacy technologies. If AI-first connection becomes the dominant intervention to loneliness, who gets left behind?

A 2024 study of nursing home residents during the pandemic is an example of this digital divide. While some meaningful video calls through Zoom and virtual reality meetups reduced loneliness for the more techy residents, those with limited digital literacy or access often found themselves more isolated than before, watching others connect while struggling with interfaces designed for digital natives.

Also, while the EU Loneliness Survey attempted to include digitally excluded populations through phone-based interviews and sampling quotas, the 2024 methodological report reveals that older and less-educated individuals remained underrepresented in final datasets, even after weighting adjustments. This suggests that tech solutions may struggle to account for those most at risk of chronic isolation.

The Quality Question

Perhaps most critically, the research suggests that digital tools work best at maintaining existing relationships but struggle to form new, intimate bonds. A 2022 umbrella review of technology interventions found only “moderate to low evidence” that ICTs reduce loneliness, and noted they were “less effective for new connections compared to existing ones.”

The Presence Paradox

Across the current literature, there is another idea that keeps cropping up: loneliness is not simply about contact, but about felt presence, the sense of being fully seen and emotionally attended to. A 2024 policy brief from the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre puts it simply: “technologies are seen as both enhancing and inhibiting connections,” because they cannot fully replicate the psychological sense of co-presence.

This presents a philosophical challenge. If loneliness is at its core the absence of felt presence, that sense of being truly “with” another person, can technology, no matter how sophisticated, move beyond that gap? Or are we creating illusions of connection that may delay the harder work of building real relationships?

The Unintended Consequences

Early research on AI-powered companionship is disclosing another trend: users often report that virtual relationships feel “safer” and “easier” than human ones. Some users have even admitted to withdrawing further from the unpredictability and challenges of real-world intimacy. One user wrote, “There’s no judgment, no bad days, no awkwardness. It’s perfect— and that’s the problem.”

Are we moving into a kind of “emotional outsourcing” where we delegate the work of connection to algorithms, potentially diminishing our capacity for the messy, difficult, but ultimately rewarding work of human relationships?

SDG Lab’s Response: We’re Not Replacing Relationships but Expanding Them

Kudos doesn’t shy away from these criticisms but engages with them directly. His response reflects a company that has thought about the ethical implications of virtual intimacy, and rather than being put off, has restructured them as design challenges.

On the accessibility question, he pushes back against the idea that older or less digitally fluent users are inherently excluded. SDG Lab’s platforms, he says, are designed with usability in mind, and he argues that adoption often exceeds assumptions. “Older users are just as adept and open to technology as their younger peers,” Kudos said, citing DateMyAge, a product of SDG, as proof. The company has reported that 90% of its users are engaging in video dating. He emphasizes that exclusion is often the product of poor design, not age. However, this success raises questions about whether older adults are truly “just as adept and open to technology as their younger peers,” as Kudos claims, or whether they’re simply adapting out of necessity as the “traditional” physical spaces for chance encounters disappear.

He also challenges the notion that virtual intimacy is inherently engineered for surface-level conversations and potential addiction. SDG Labs, he says, deliberately avoids product features that optimize for time-on-app. Instead, the company designs for what Kudos calls “ethically sound purposes” and “healthy interaction patterns,” features that encourage slower, more purposeful interactions.

“Our goal is not to generate maximum engagement, but to promote genuine connection.”

he explains.

That includes resisting the urge to gamify relationships or promote constant stimulation.

Perhaps most telling is Kudos’s reframing of the “bandage versus cure” debate. The real issue, he argues, may be that traditional relationships are already failing to meet modern emotional needs.

“Despite the idea that romantic partnerships are the foundation of emotional well-being, many of us are struggling even within those close connections,”

he says.

Virtual intimacy, in his view, isn’t a replacement but an expansion: one that amplifies access to connection across geography, identity, and life stage.

These questions aren’t meant to dismiss Lab’s vision. The company may very well be the revolution that our society needs, even if we don’t fully understand it yet. For Kudos and his team, AI companionship isn’t ‘less than’ human. This type of connection allows people to be more vulnerable, authentic, and introspective in a safe space. And in our current climate, don’t we all deserve the safety to be ourselves, fully?

Maybe the real question isn’t whether virtual intimacy can reduce loneliness. The research suggests it can. But also, maybe not. The question we should be asking is whether it can do so without fundamentally changing what it means to be human, together.