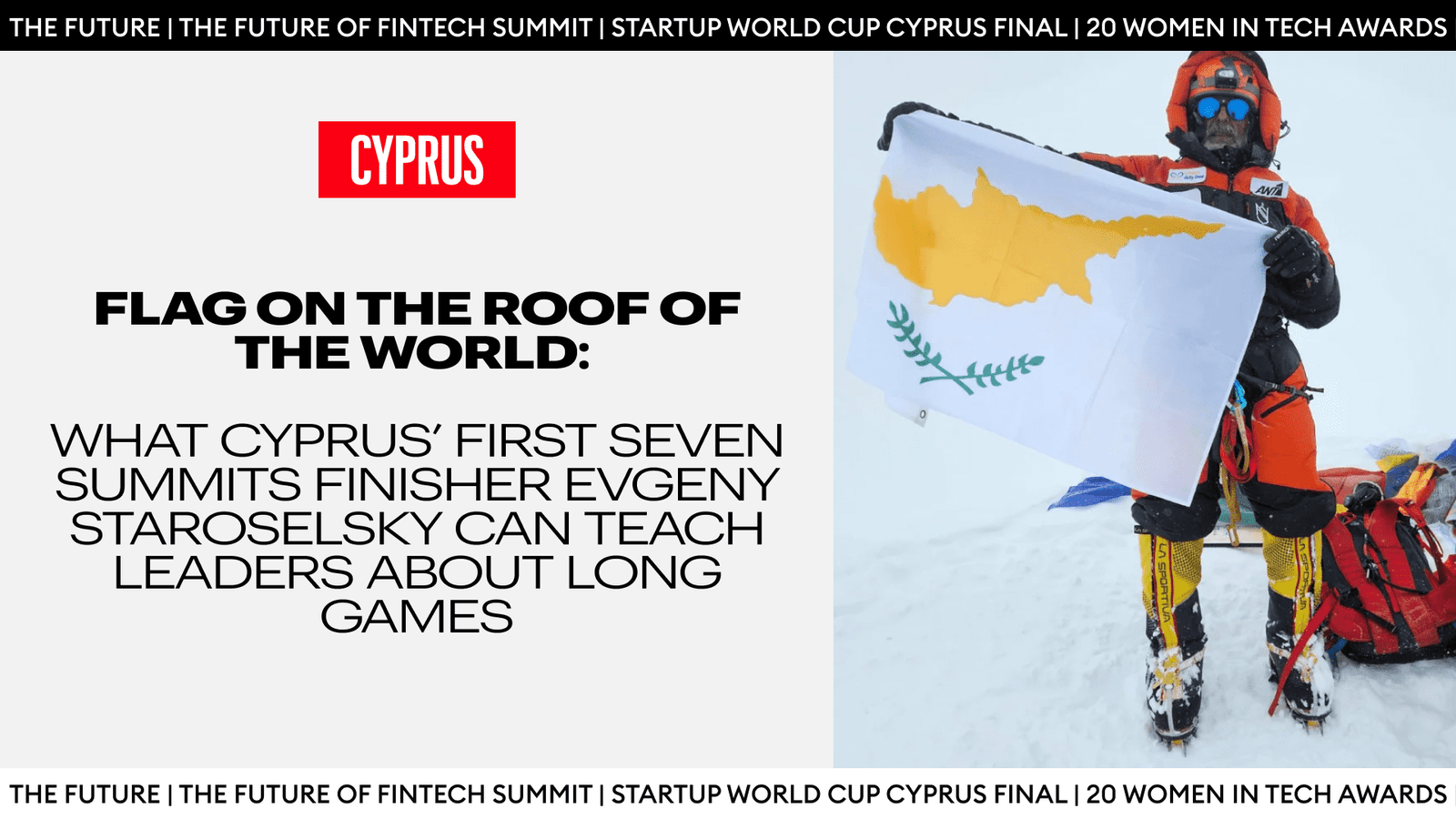

On 13th October 2025, just after six in the morning local time, Evgeny Staroselsky stepped onto a narrow limestone ridge in the Indonesian Papuan highlands and raised the Cyprus flag. The summit, standing at nearly 5,000 metres, was the Carstensz Pyramid, Oceania’s highest point, and it was the final piece in one of mountaineering’s most coveted challenges, The Seven Summits. This challenge, whereby mountaineers climb the highest peaks on every continent, is a kind of world tour of extremes, from Everest on the Nepal–Tibet border and Aconcagua in Argentina to Denali in Alaska, Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, Elbrus in the Caucasus, Vinson in Antarctica, and Carstensz Pyramid in Indonesian Papua. Only around 500 people have completed this challenge to date, and now, the name of the first Cypriot citizen, Evgeny Staroselsky, sits on that very short list.

In 1985, American businessman Richard ‘Dick’ Bass became the first person to climb the highest peak on each of the seven continents, a feat he later chronicled in his book Seven Summits, co-written with Frank Wells and Rick Ridgeway. A year later, Italian climber Reinhold Messner argued to replace Mount Kosciuszko in Australia with the more technically challenging Puncak Jaya (Carstensz Pyramid) in Indonesian Papua, treating “Oceania” rather than just Australia as the continent. Over time, most serious alpinists have come to treat this “Messner version” as the standard. Because there is no governing body for the Seven Summits, the numbers are stitched together from private registries and guiding companies rather than an official database. It is a niche within a niche: thousands of people now stand on Kilimanjaro each year, but only a few hundred have ever completed all seven continental high points into a single life project.

Follow THE FUTURE on LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, X and Telegram

For business leaders reading this, the relevance goes beyond the romance of ice and altitude. The Seven Summits are a long, expensive, multi-year undertaking with real downside risk. They force you to think in programmes rather than trips, to prepare with a margin, and to make hard decisions under pressure when conditions change. The mindset is not so far from building a company, steering a turnaround, or betting on a new market from a small, peripheral base like Cyprus.

In this interview with The Future Media, Evgeny Staroselsky shares how he finished the Seven Summits from an island at sea level, why he chose to carry the Cyprus flag to some of the harshest places on Earth, and what years on the world’s highest mountains have taught him about preparation, risk, and resilience.

You’ve just completed the Seven Summits, finishing with Carstensz Pyramid as your final peak. What was that last ascent like, and why was this summit so important to you personally?

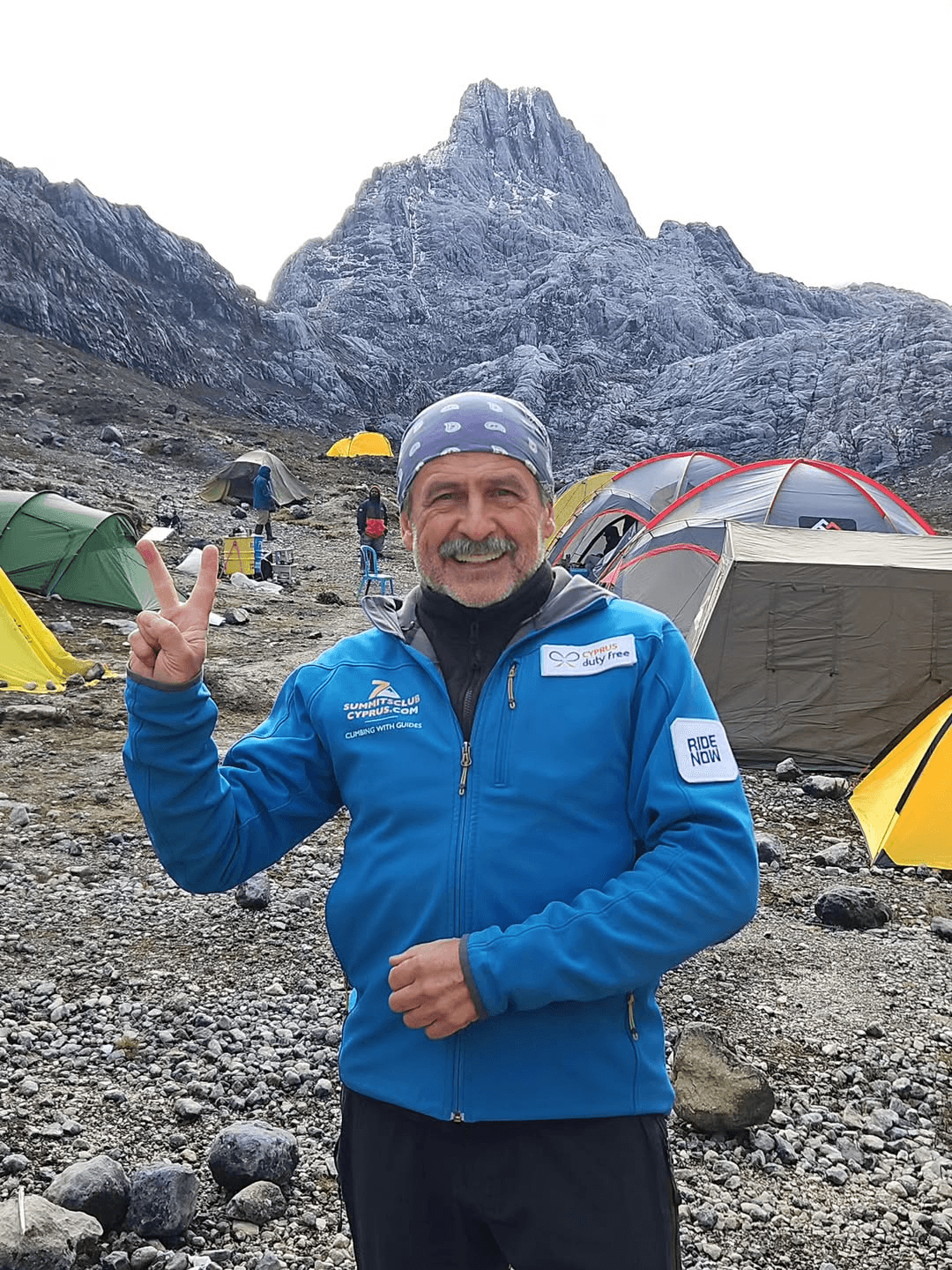

Carstensz Pyramid was the last, unfinished chapter in my Seven Summits programme, the one unfinished peak that was still waiting for me. For years, it was impossible to enter the region. In 2019, it was closed to foreigners because of local conflict around the gold mine. It was only recently, in 2025, when they finally reopened it again, that everyone who had been stuck with an incomplete programme rushed to get there. I was one of them.

The journey there was long. First, we had to reach a small town called Timika. Their life revolves around two things: the huge Grasberg gold mine and the mountain. For most outsiders, you come here either to work at the mine or to head for Carstensz. Nothing else really happens there. From this town, the real journey begins.

I went there with the Elite Exped team, the same people I climbed K2 with. Their leader is Nims, a Nepalese climber. In 2019, he made a real breakthrough in alpinism. In six months and six days, he climbed all fourteen eight-thousanders. Before that, even Reinhold Messner, a legend of world mountaineering, needed over eight years to do the same. This says everything about the level of this guy and his team.

Carstensz itself is not very high compared with Everest or K2, but it is a beautiful and technical mountain, with steep rock and real climbing. We set off in the dark, around two in the morning, from the base camp. The weather there is classic equatorial weather. It usually pours all night, eases off by morning, and by evening the rain returns again. For the climb, you have to slip into that short dry window, go up, touch the summit, and get back before the next wall of rain arrives.

We were lucky with this window. We climbed from base camp and reached the summit at sunrise, around six in the morning on 13 October 2025. I raised the Cyprus flag there at the top. My Seven Summits story was finally finished.

Until the start of 2025, only about 231 people in the world had completed the Seven Summits in the Carstensz, or Messner, version. Now one of them is a Cypriot citizen. I am also the second Ukrainian to have completed it, too. Cyprus is my second motherland, and taking its flag, and the flag of my homeland, to the last of the seven highest points means a lot to me.

Let’s go back to the beginning. Where did you grow up, and what kind of environment shaped your early interest in the outdoors and climbing?

I was born in Kharkiv, Ukraine. All my life, I have had what we call a “needle in one place.” I couldn’t sit still; I was always moving, traveling, yearning for the extreme. At one point, I even considered attending a nautical school in Kaliningrad, but that didn’t happen. I believe it is that same restlessness that later pushed me toward the mountains.

My real start in climbing was at university. There was a mountaineering club, and my friends dragged me there. During our first year, we went on our first trip to the mountains, to Elbrus. This was back in 1979.

I was hooked after that. I kept going, while most of the guys I started with left the sport sooner or later. After finishing my diploma at university, I also applied to become a professional coach. I became a guide, an instructor, a rescuer. Up until about 1996, that was my full-time job. Later, I started a construction business in Ukraine, and my experience of the mountains was limited to one or two big expeditions a year. But the yearning was still there.

I completed all five of the 7,000-metre peaks of the former Soviet Union, and the media began to call me the “Snow Leopard.” Later, I started a construction business in Ukraine, and my experience of the mountains was limited to one or two big expeditions a year. But the yearning was still there.

How did you turn mountaineering into a business from Cyprus, and how do you actually find the clients who join your expeditions?

We moved to Cyprus in 2011. It was an opportunity to start over and a chance for me to return to the big mountains again. I could’ve gone back into business, but I understood that if not now, I would never do what I really love.

There was some sport rock climbing on the island on artificial walls and a bit on real rock. Now it’s developed more, and the places are actually quite good. But real alpinism was basically zero. So, I started to push this direction. Little by little, and with a lot of time and patience, I began organising expeditions, starting with the more beginner-friendly high mountains like Kilimanjaro, Elbrus, and, before the conflict, Ararat. These mountains are not technically very difficult, but they do give a real altitude experience.

Little by little, I saw that there are people even here who want this. Now I even have two or three clients preparing for serious goals like Everest. I feel it is time to share my knowledge and experience, and Cyprus gives me that possibility.

For beginners who dream of their first major mountain (Kilimanjaro, Elbrus, Ararat), how do you know when they’re physically and mentally ready to take on that challenge?

First of all, everything should go from easy to more difficult. You must not climb a mountain you are not ready for. I’ve said many times that you have to be prepared for the mountain you choose.

My recommendation is to always start with the less technical high mountains, so peaks of around five to six thousand metres. For example, Kilimanjaro, Elbrus – although, unfortunately, I don’t go there now because of the war and because Elbrus is on Russian territory – and Ararat. These are what we call “easy” mountains, but they let a person feel like they are in the mountains and understand how their body behaves at altitude. My work is to help them acclimatise properly and help them go through it correctly.

If I may brag, I have been taking clients to Kilimanjaro for over ten years, and in all that time, only one person didn’t reach the summit. Everyone else did. Usually, I take one or two groups a year, which means roughly 15–20 people a year. So, you can do the maths. This February, for example, a 65-year-old Cypriot woman reached the top with me. That is just the result of proper preparation and approach to the client, not magic.

Then there is the mental side. You can’t push anyone into the mountains. Someone might like the mountains, someone else likes diving, playing chess, or checkers. You try different things and then decide what is really yours. If you go to the mountains once and say, “This is not for me,” that’s fine. If you tried and said, “This is mine,” that’s also fine. What I don’t accept is when someone criticises something they’ve never even tried.

Maybe that’s why it makes me so happy that about 60–70% of those who have gone to the mountains with me continue to go back again. Some say, “Thank you, that’s enough, I’ll stay here, go to bars, enjoy myself,” and that’s their choice. But most of them, as we say in Ukrainian, “get infected,” their eyes light up, and they ask, “So, when are we going next?”

What kind of training do you personally do to prepare for a climb, especially now that you live at sea level in Cyprus?

I’ll talk about how it looked preparing for the last summit (Carstensz Pyramid). The altitude is under five thousand metres, so my training is quite relaxed. In my career, I have completed 13 seven-thousanders, three eight-thousanders, and spent a lot of time at altitude. To give you a comparison, for beginners, hypoxic symptoms usually start somewhere around three thousand metres. In my case, they start higher, around four and a half. At three thousand, I feel absolutely normal. And that’s why my preparation for heights of four to five thousand metres, I treat it pretty casually.

But in general, my training combines technology with physical work. When I’m home in Cyprus, I train six days a week with acclimatisation work, which I use hypoxic systems machines for. They help you acclimatise here at sea level and “lift” you to the altitude you need, from about 2,500 to 6,000 metres. You can do a full training session on a treadmill or on the stair machine with a mask on, and the machine feeds you air with reduced oxygen content.

There is also the option of a hypoxic tent. You sleep inside it, and the system creates the same atmosphere as at a chosen altitude. A training programme is built, and in this way, you prepare your body and your mind for more serious tests in advance.

On the more “normal” physical training, I do a couple of routes in Troodos a few times a month. Before, I used to run three or four times a week, five to eight kilometres. Now I have a problem with my knee, so I protect it – I “live on tape”, as we say – and try to run less, especially on asphalt. I still walk, but I try to minimise running.

I go to the gym four times a week. Three times a week, I do whole body training plus either bike or stairs, where I work carefully to protect the knees. One session a week is a big aerobic load, with again, bike or stairs.

When I prepare for a serious mountain, I switch to six training days a week and stronger aerobic work. The general physical training stays more or less the same, but the aerobic part changes. I use my hypoxic mask and machine more, increase the distance and the time in Troodos, and add interval work. The idea is to train the heart and lungs, increase lung capacity, and teach the body to work under stress.

That’s my system.

At some point, you began carrying the Cyprus flag to some of the highest places on Earth in a project called “Flag of Cyprus on the highest top of the world.” When did that idea first come to you, and what does that flag represent for you on a summit?

I was already living here when I decided to take on the Seven Summits program. In 2018, I received my Cypriot passport, and that’s when the idea came to me to take the Cyprus flag to the highest peaks of the world. Since then, the Cyprus flag has been with me on all the highest points of the continents, including Everest and K2, and on many other mountains that are part of the programme.

Why this flag? First of all, because I live in Cyprus, it has become my second homeland. I run all these projects from here, so for me, the Cyprus flag is symbolic. I also carry the flag of Ukraine with me, but I share those photos privately because of the current conflict. I don’t want to be political in my endeavours. I want what I do to bring people together, not divide them.

Which has been your scariest or most difficult experience in the mountains, and how did it change you as an alpinist and as a person?

If we talk about the most difficult mountain, then of course it’s K2. People call it “The Savage Mountain” for a reason. Mount Everest is the world’s highest peak, almost 9,000 metres, whereas K2 is shorter at 8,500 metres. But K2 is far more treacherous, more rocky, and averages 45 degrees from base to top.

If you look at the numbers, Everest has had around 11,000 ascents. On K2, there have been fewer than 800. At the same time, roughly 300 people have died on Everest, and on K2, the number of deaths is only about twice smaller that, with many times fewer climbers. That already shows what kind of mountain it is. So maybe “scary” is not the right word. I would say it is the toughest and most demanding.

Another peak that left a very strong mark on me is Khan Tengri, a seven-thousander in the Tien Shan. I love that mountain. I’ve been there seven times. On that same peak, we won the USSR championship in 1990. The wall starts around 4,200 metres and finishes at 7,000. Almost three kilometres of route and about two kilometres of steep climb, with an average angle of around 72 degrees. We spent two nights hanging on that wall at a height of 6,000 metres. You can’t even put up a normal tent there – you just hang on the rope, cover yourself, clip in, and try not to freeze. Even now, I remember that route as if it were last month.

Experiences like that remind me of what my teacher, Yuri Ivanovich Grigorenko, used to say. In the mountains, you must always be “one step higher,” and you need a reserve. You must be prepared better than the minimum you expect from the mountain. Then, when something unexpected happens, fear still comes, because fear is normal for any person, but for a trained professional, it lasts seconds or minutes and then passes. Then, you start to analyse the situation and make decisions.

People who are not ready for the mountain let fear turn into panic, and panic in the mountains makes you a victim.

What’s next for Evgeniy Staroselskiy? Will you be taking a break from the mountains?

I’m already itching to return! I am preparing clients now for Everest and Kilimanjaro, and that will be happening next year and the year after.

Recently, I opened my own company in Tanzania, on Kilimanjaro, with a local partner. We have a strong team, including an excellent cook and guide. We have already taken the first three groups, and now we are preparing for the upcoming season.

I’ve also founded the Survival Academy Cyprus for both youth and adults. There, I teach important survival skills when out in nature, sharing my years of experience and knowledge from my time in the mountains. Our camps are constantly getting booked up as soon as I announce new dates.

I had promised my wife that I would take it slower after the big challenge of the Seven Summits. But how do I explain this? The mountains are calling. They are part of my being. I cannot deny that.