Women live longer than men, but not necessarily better. In the EU, women can expect to live five years more than men, but those extra years for most are spent in poor health. For instance, in Germany, untreated menopause symptoms are directly linked to around 40 million sick days a year, which results in an estimated economic loss of 9.4 billion euros. Across the pond, employed women in the United States pay approximately 15 billion dollars more out of pocket for healthcare each year than employed men. This number excludes maternity care.

Closing that gap, however, has historically been a low priority for public and private R&D budgets. In 2020, only five percent of health R&D funding was directed to women’s health, and just one percent to non-cancer conditions such as endometriosis, preeclampsia, pelvic floor disorders, and menopause. The number of women included in clinical trials is also lagging. An analysis of more than 1,400 US drug and device trials run between 2016 and 2019 found that only 41 percent of participants were women, with underrepresentation in crucial areas like cardiovascular and mental health, where women often bear a higher disease burden. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that women are 1.5 to 1.7 times more likely than men to experience an adverse drug reaction.

Follow THE FUTURE on LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, X and Telegram

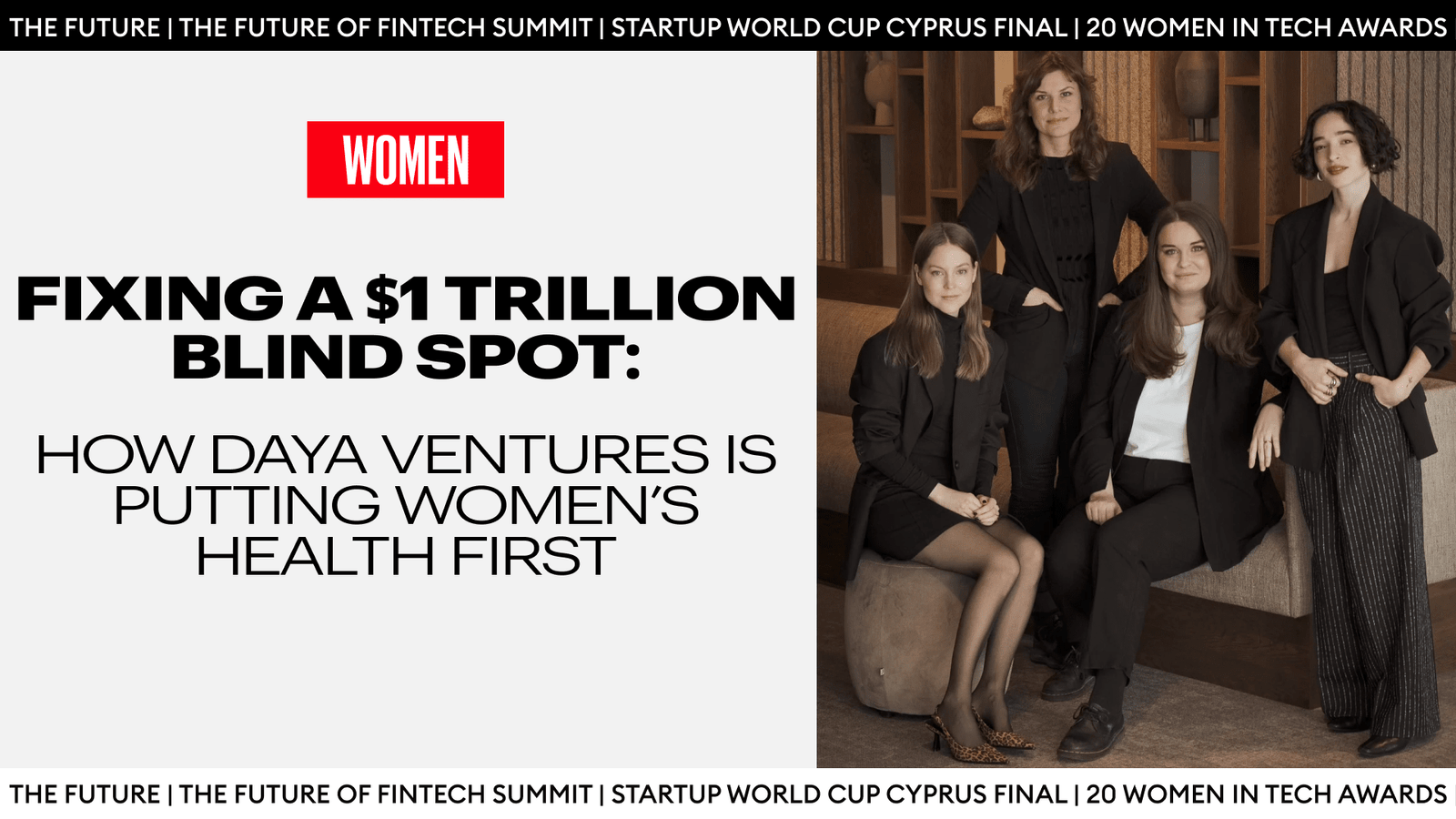

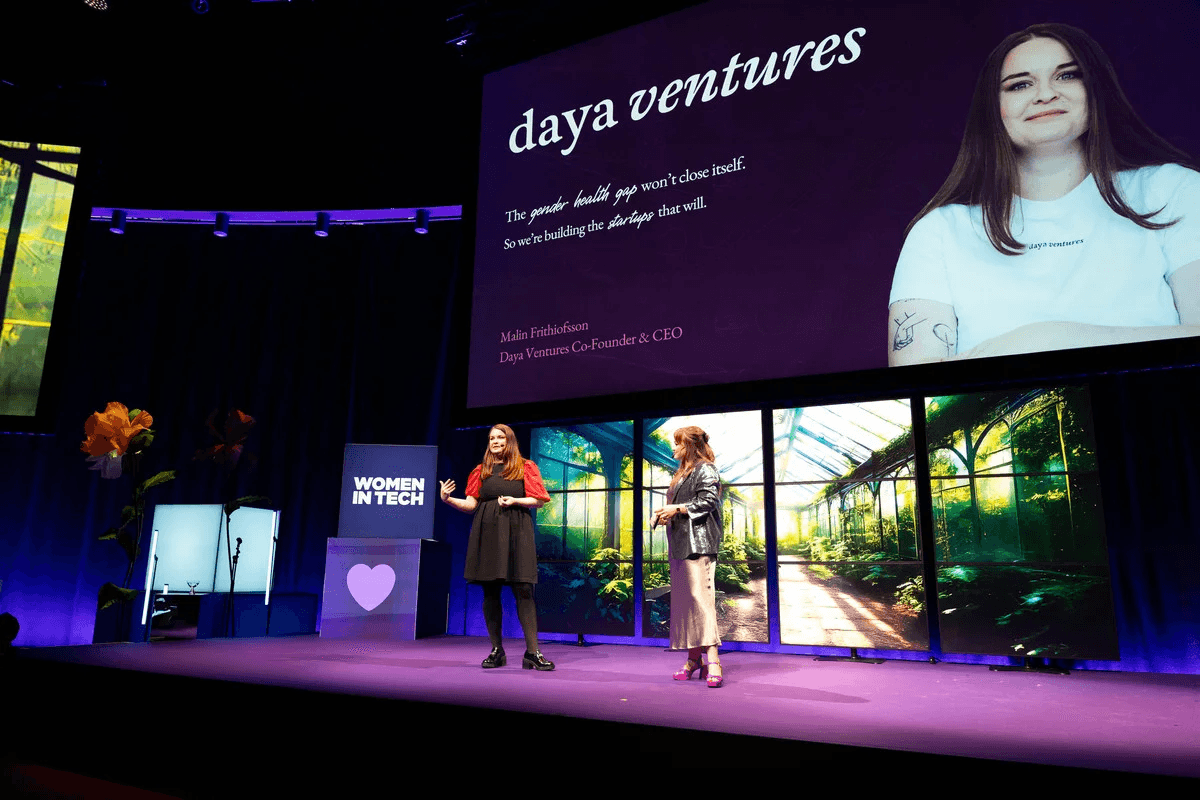

These are just a fraction of the systemic discrimination against women’s bodies; yet, they are enough to evoke shock, frustration… anger. For Swedish entrepreneur Malin Frithiofsson, it wasn’t enough to react; the more she researched, the more she knew it was time to act.

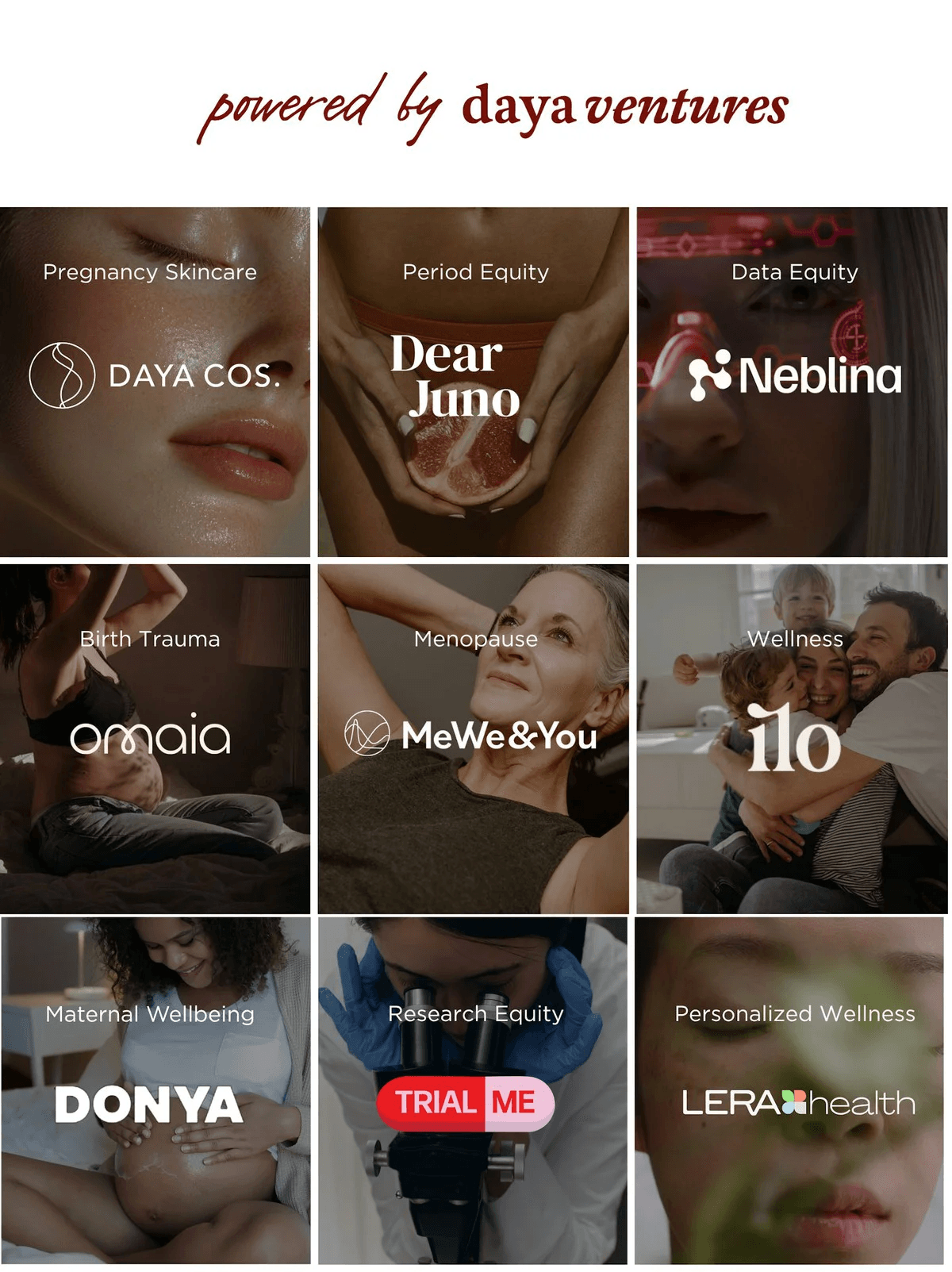

Her answer was not to wait for solutions to appear. It was to design a different way of creating them. At Daya Ventures, she and her team start with a problem in women’s health, a clinician who sees it every day, and the lived experience of patients, then build companies around that triangle.

This is happening in a funding environment where femtech still attracts only around one to two percent of global health tech venture capital. Daya’s model is a response to that scarcity. Instead of assuming that innovation will trickle down to women’s bodies eventually, it asks what happens when you start from unmet need and work forward to the technology.

In this interview with The Future Media, Malin explains why “move fast and break things” is dangerous in women’s health, and why the most scalable innovations begin not with technology, but with trust.

When did you first become aware of the gap in research and solutions in women’s health?

I spent six years helping commercialise deep-tech research. And in all that time, I don’t think we had a single startup in women’s health. I may be wrong, but I doubt it.

Personally, the wake-up call came when I developed preeclampsia during my first pregnancy. Here I was, someone who had been working for years, working with researchers at the forefront of deep-tech innovation, suddenly facing a condition that we still don’t fully understand, with no cure, and yet 500,000 women are dying from it globally every year. I remember thinking, Why are we just accepting that?

That’s not a growth mindset. That’s acceptance. That was when the frustration began to grow. It wasn’t just about my experience. It was about the layers of neglect. We don’t have as many female researchers. The female researchers and women’s health institutions we do have don’t get the same amount of research funding. By the time something reaches investors or founders, the options for me as an ambassador are already next to nothing.

That is when we, my co-founders and I, realised we can’t just be an investor or startup. If we want real change, we can’t wait for the end of the line. We have to go to the very beginning.

So, for somebody who hasn’t come across your organisation, what is Daya and its mission?

Daya is a venture studio, but not the usual kind. Our mission is to make women’s lives better through venture creation by bridging the gender health gap.

We don’t wait for founders to come to us with ideas. Instead, we start with the problem. That can be birth injuries, preeclampsia, endometriosis, or menopause care. We bring together researchers, doctors, and patients in order to ask if there is space for a tech solution to solve some of these issues. If the answer is yes, we build the prototype, file the first IP, test the model, and develop the brand. Then we recruit the founding team to take it to market. It’s a very problem-oriented system.

We have over 700 experts in our network. Every time we work with someone, we invite them to stay in our community. Now our brand has spread, and researchers invite each other through word-of-mouth. That way, when a new problem arises, we’re not starting from zero.

But we do at times complement the new team with one or two people outside of this community, especially when it’s a very specific women’s health issue, and we don’t have anyone in our circle working in that research area.

How do you prioritise the problems?

It’s absolutely the hardest part for the team and me. We’re all very passionate, all entrepreneurs, all want to run fast. And when you see a problem, it’s very hard to say: OK, we have to wait, because we’re already working on three others.

So no, this is not purely data-driven. I wish it were. It’s very personal.

For example, I’ve already mentioned my experience with preeclampsia. That was the problem we started with. I had just lived it, so I was frustrated, angry, and yes, I used my power to direct our resources. But that’s where our passion and drive come in because health is very personal.

More recently, we’ve added market reverse engineering to our approach. So, looking at what is the biggest liability payout for health insurance in Europe? Cancer is, of course, number one, but what’s next? What are the other very high liability payouts?

If we build there, then we know we are targeting both an unmet need, and we will have an easier time getting the product to market, for our solution saves money for insurance companies. It’s a built-in business model from the start.

Our goal is still always to reduce suffering. Too much of women’s healthcare is out-of-pocket, even though as women we pay the same amount of taxes. So, we look for solutions where we can save costs for employers, insurers, and the public healthcare system, but the patients don’t have to take on the financial burden themselves.

We have a heat map that we update annually based on the different types of technologies and women’s health areas. We are trying to find the right space where we can have the most impact, financially feasible, and a sustainable business model.

Do you focus your market exclusively on Europe, or is it more global?

We are primarily focused on Europe first, but every startup we build has global intent from day one. You can’t stay a unicorn only in Europe.

Right now, we have two U.S. startups in the portfolio. Earlier this year, we opened our subsidiary in Nairobi, focused on East Africa.

They build primarily for the regional context of East Africa, and we build primarily for the regional context of Europe. But all of these startups should have a global end goal.

Why Nairobi? Because women’s health does not look the same there as it does in Gothenburg. If we built everything in Sweden and shipped it out, we’d miss critical cultural context, like the fact that, for mental health support, many women in East Africa turn first to religious leaders, not therapists. That’s not something you can find on Google. That’s something you learn by being there.

So, we focus on regional hubs, global ambition. Each hub builds for its cultural context but learns from the others.

What type of support do you offer the founders you recruit?

We work in three main stages.

The first is what we call the Ideation stage, where we do interventions with researchers, doctors, and patients to validate the problem.

After approximately six months, we move to the Venture Creation stage, where we build the prototype, file the IP, create the landing page, and define the go-to-market. The founding team can join at the start of this phase or toward the end. It depends on how quickly we find the right people.

Once all of the essentials are in place, we run a six-month Acceleration phase. This is open to all of our startups, and even to select external startups. That is, startups that we haven’t created but are moving towards their final pitch. We don’t have a rulebook setup.

We listen to what the founder needs, whether it’s fundraising support, reaching early customers, or working on their pitch. It’s not a one-size-fits-all approach. We listen and then adapt.

Who is on your core team?

It’s a small but growing team.

The ideation stage is led by Gerhard Bothma, our only man in the core team, which honestly says a lot about how amazing he is. He works closely with our innovation fellows, who rotate every 12 months.

My co-founders are Jenny Lundkvist, Chief People Officer, who assembles the founding teams that actually win, from first hire to leadership bench, and Jennifer Grönqvist, Chief Innovation Officer, who is head of all clinical partnerships. That is a critical stage for us, setting up hospital and clinic relationships can take startups one to two years. We do it for them, distribution and pilot partners, so they can launch faster.

Then there is our incredible team who work tirelessly across our ventures:

- Victorine Lançon, CCO, creates brands with soul and strategy, shaping how our ventures look, feel, and connect with the world.

- Elina Åkerlind, CFO, keeps us investor-ready and runway-smart while modeling the path to sustainable growth.

- Sophia Pagil, IP Lead, ensures defensibility in our ventures.

- Ute Michaela Arndt, Product Lead, makes sure what we launch sticks.

- Josefine Hovmark, Tech Lead, ships the first usable prototype from TRL 0 to 3.

- Stephanie Darvill, Head of Acceleration, guides startups from launch to revenue.

- Our three startup coaches, Håkan Axelsson, Malin Kjällström, and Mina Lindberg, support founders in strategy, fundraising, and scaling.

You’ve just announced that Daya Ventures is opening part of its ownership to your own community and to non-professional investors. What exactly are you doing? What are the core ideas behind this community investment round?

The decision to do a community investment round is grounded in three core ideas:

Number one is because women should own more. Women own less of everything: companies, land, and capital. Allowing them to invest directly in Daya means shifting from being participants in innovation to being owners of it.

Number two. Ownership drives equality. Less than 3% of venture capital goes to all-female teams, and even in impact investing, most capital flows to traditional structures. Inclusive ownership isn’t charity – it’s a smarter, fairer way to build long-term value.

And finally, because impact should be co-created. Most impact investing happens after the innovation is built. Daya is flipping that logic: letting those who create and benefit from the innovation become shareholders from day one.

Daya’s current portfolio is 98% women-owned, a reflection of its founding belief that equity (social) requires equity (financial). The community investment round is the next step in that same philosophy, extending ownership to a broader group of contributors and supporters.

The round is conducted through Seedrs (Republic Europe) under FCA oversight, using a nominee structure that enables both new and experienced investors to participate responsibly.

What does diversity in the women’s health tech ecosystem look like for you?

We work from an intersectional feminist perspective, which means we recognise that women’s health does not look the same for every woman. It’s not just that you’re a woman. Your experience of the world is different depending on your race, class, geography, disability, sexuality, all of it.

We saw this during a recent endometriosis intervention. Women of colour told us they had been told by doctors, “It’s normal, you know, black people bleed a lot.” That’s not just a misdiagnosis. It’s systemic dismissal. There’s a misunderstanding of the female body, and some bodies are far more misunderstood than others.

Diversity is built into our process. Women’s lived experience is so vast, and we need to respect those nuances. That is why at the ideation stage, we work with experience-based design. We bring those varied sets of experiences into the room because otherwise we will only get the lived experience of one set of women, which is not the result we want or require. If the room reflects one kind of woman, the solution will fail the rest.

That is also why we chose to open a hub in Nairobi rather than scale more startups in Gothenburg. We needed to build different ones with direct experience of women’s health in their geographic region. Women’s health in East Africa is not a reflection or a translation of our own here in Sweden. We work with a model where local entrepreneurs and the women in the ecosystem have ownership of the stories of their bodies and businesses, rather than a prescribed formula of how their bodies should work.

For instance, one of our first startups in the region is building a burnout prevention app, which is a major health issue in East Africa. Our go-to-market strategy for this app looks very different than theirs. Something I was not aware of was that the religious leaders there are most often the locals’ first points of contact for any mental health issues. The local entrepreneurs would need to find ways to work with that potential channel to help reach women in need. It’s these fine cultural differences that affect physical and mental health, reproductive rights, and so on that are crucial in building equity within women’s health.

How do you approach data protection, consent, and ethics when you are building in women’s health?

In this space, data protection and consent are absolute non-negotiables. We’ve made it a standard rule for our startups. Integrity has to be built in by design. It’s not an add-on. That includes everything from the prototype to the vendor choice. And frankly, we would never ship something if it wasn’t 110% safe and passed our scrutiny.

I am glad to see more and more discussions around data protection and ethics happening this past year, both online and offline. Last year, we ran a workshop on the importance of data integrity, and the conversations were already happening. This was before the big lawsuits where companies like SL Data Services and Google had to pay for leaking personal health data. It’s damaging if it’s credit card info. When it’s abortion history, sexual health, or trauma records? It can be dangerous.

We’re in a moment where reproductive rights are under threat—not just in the U.S., but in the U.K., and closer to home. So every product we build must ask: Could this be weaponised?

Yes, you might design an app to help women track symptoms. But could it be used to police abortion? Could data be subpoenaed or leaked? Misused? You have to think five steps ahead.

That’s why “move fast and break things” is the worst possible mantra in women’s health. You don’t get to “break” here when we’re talking about lives.

Can you share some of the stories of some of the startups that you have birthed, even at this early stage?

All our startups are young; the oldest is just one year old. But they all speak to how women’s health is connected to economic and social systems.

One of these startups is called Omaia. The idea for the startup originated from an intervention we led on birth injuries. Research shows that fear directly increases the risk of birth injuries. Stress hormones stall labour, which can lead to emergency C-sections, prolonged births, and trauma. The effects didn’t stop there, though. Studies also suggested that women who experience traumatic births face higher risks of postpartum depression and are less likely to return to their pre-pregnancy jobs. And then, the kids have a higher risk of having mineralised teeth, which means that they have a higher risk of getting injured, getting a cavity. In societies like Sweden, where we pay for dental care until you’re 25, you know, what is the cost of that in society? This was not just a cost for insurance companies and individual families, but for the whole economy of the country.

What was surprising, however, was that cognitive behavioural therapy came up as the most effective treatment for birth anxiety, which translates well digitally. A low-cost digital intervention during pregnancy could reduce suffering and save millions for employers, hospitals, and insurers. That’s the kind of ripple effect we look for.

Another startup came out of a collaboration with AstraZeneca, as part of a health hackathon. The winner was Trial Me, a community platform to recruit women into clinical trials. It’s shocking that we have been chronically underrepresented in clinical trials. It was only in the 90s that we were formally included. Trial Me makes participation easier for women and helps them to both learn more about their own bodies and contribute to the science of women’s health. It also makes it cheaper for those who run clinical trials to include women. It’s a win-win.

What do you hope to achieve in the next couple of years?

We will keep building around four to five startups a year, both in our European hub and in the East African hub. Next, we want to open a hub in Asia and North America.

Our long-term vision is a global network of venture creation hubs on all of the continents that continuously build and learn from each other. Right now, we have 16 startups. Some of our startups are already collaborating. For instance, using our clinical trial recruitment platform, Trial Me. That self-reinforcing synergy is what makes our model stand out.

The goal for 2030 is to have at least 100 startups across 7 active hubs and be the largest portfolio in the world. Today, we avoid therapeutics as it’s too capital-intensive, but as we scale, some of our hubs may take on more complex areas.

Ultimately, our purpose is not just to disrupt the health ecosystem but to reduce the suffering of the community that has long been ignored or put aside. It’s time for women, and I mean all women, to take back the narrative around their bodies.