A European Capital of Culture title can look, from the outside, like a year-long festival with a fancy badge attached. But the opening ceremonies, visiting artists, and headline events aren’t the point in themselves. They’re the scaffolding for something larger. What the EU actually designed is closer to infrastructure that uses culture as a tool to reimagine the narrative of how cities function, not just how they celebrate.

The European Capital of Culture initiative began in 1985as a way to showcase Europe’s shared cultural threads, while remaining sensitive to its diversity. Since then, it evolved into a formal EU action with objectives that range from increasing citizens’ “sense of belonging to a common cultural area” to fostering culture’s contribution to the long-term development of cities.

Follow THE FUTURE on LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, X and Telegram

The process to gain the title of a Culture Capital is deliberately slow and competitive. Member states launch calls six years ahead. Cities are assessed by an independent expert panel, and the chosen city is designated four years before the title year, followed by a monitoring period that can culminate in the €1.5 million Melina Mercouri Prize.

The impact reaches beyond the cultural aspects of the local region. It’s also economic and urban. In a 2025 evaluation, the European Commission reported that between 2013 and 2022 host cities staged, on average, 1,000–1,200 activities per title year, reaching an audience of 38.5 million people in total. In selected cities, visitor numbers increased by 30–40% on average, lifting international visibility and cultural tourism. Just as importantly, the Commission frames the action as a driver of investment, inclusion, and cooperation, the effects of which reverberate even after the closing ceremony.

In this interview with The Future Media, Kelly Diapouli, Artistic Director of Larnaka 2030, explains why the European Capital of Culture title is a tool for long-term transformation rather than a festival year, how participatory culture can reshape urban economies, and what it means to embed artists as permanent civic actors rather than short-term content creators.

1. Before we get into Larnaka 2030, can you walk us through your own journey, from working on the Cultural Olympiad and Eleusis’ European Capital of Culture bid to founding Busart, and how those experiences led you to become Artistic Director of Larnaka 2030?

I was born and raised in the centre of Athens in the years immediately following the restoration of democracy in Greece. It was a period shaped by hope and a strong belief that societies can actively work towards a more just and inclusive future. This mindset has deeply influenced my thinking and professional choices.

I studied theatre at the University of Athens, followed by a master’s degree in European Cultural Policy and Administration at the University of Warwick. Early in my career, I worked with the Cultural Olympiad, focusing on international cultural networks and large-scale collaboration. This is where I learned to see culture not as isolated projects, but as ecosystems built through relationships, trust, and shared purpose.

When the organisation closed in 2008, I founded Busart to continue this work independently. A defining moment was organising the IETM (International Network for Contemporary Performing Arts) Plenary Meeting in Athens in 2013, entitled “Tomorrow.” At the height of the financial crisis, it brought together around 500 artists and cultural professionals from across Europe to collectively rethink the future, demonstrating how culture can generate resilience, dialogue, and new imaginaries in moments of crisis.

This trajectory led me to the European Capital of Culture process in Elefsina, which won the title among 14 candidate cities. This result came as a shock to the Greek cultural landscape, where culture is often still perceived primarily as heritage or institutional programming. Elefsina showed that culture can also be a driver of social change, environmental responsibility, and economic transformation, and that smaller, post-industrial cities can compete with strong, future-oriented narratives.

Larnaka 2030 is a continuation of this trajectory.

I see the role of an Artistic Director fundamentally as that of a networker: someone who creates the conditions for people, institutions, communities, and ideas to meet and produce something larger than ourselves. Community-based work, participation, and long-term transformation have been at the core of my practice, and they define my approach in Larnaka today.

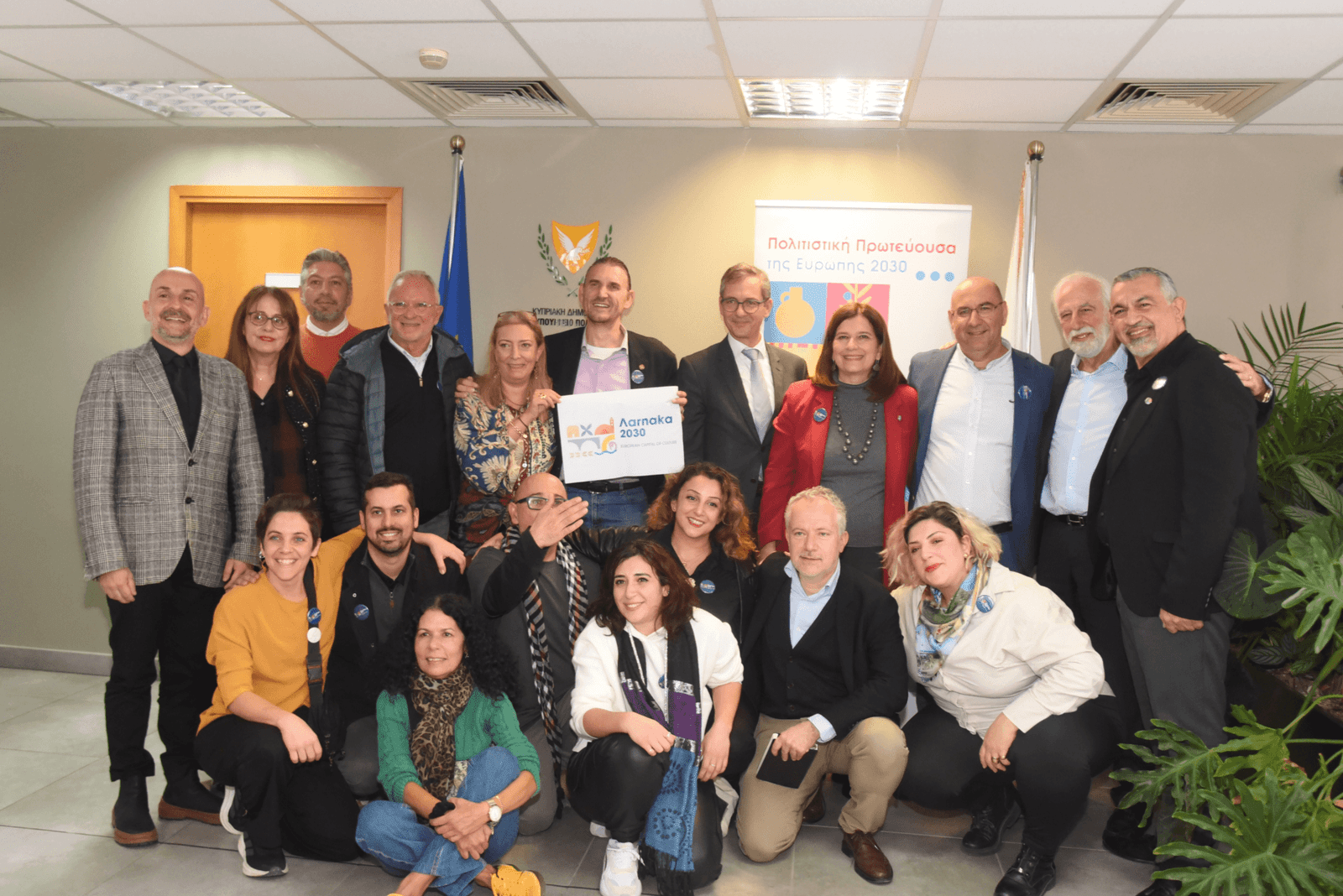

2. How did it feel when you heard Larnaka had been recommended as European Capital of Culture 2030, and what does that title mean for the city?

It was a deeply rewarding moment, a real sense of joy that came from three years of focused, collective work. More than a personal feeling, it was a shared moment of recognition for everyone who believed in and invested in the idea of Larnaka as a distinct cultural place on the international map.

What makes this achievement truly special is its collective nature. It brought together institutions, professionals, communities, and citizens around a common vision. Beyond tourism headlines, the European Capital of Culture title is about long-term transformation: strengthening cultural infrastructure, building trust between stakeholders, empowering local creativity, and shaping a more inclusive and confident city. Real change happens only through collective endeavour, and this is exactly what Larnaka 2030 represents.

3. The bid is built around “Common Ground” and the idea of anthropia – our shared humanity. How do you explain that vision to someone in Larnaka who isn’t from the arts world?

We are living through a period of intense polarisation, climate crisis, and social fragmentation, a moment when our shared humanity feels under pressure. Common Ground and anthropia — the Greek word for humanness — are a simple but urgent response: a call to reconnect with what we all share, regardless of background, belief, or origin.

For someone outside the arts world, this means putting care, sustainability, and democracy back at the centre of everyday life in the city, not as abstract values, but as priorities that shape how we plan, govern, and live together. It is about investing in the city’s “soft powers” — culture, trust, knowledge, social cohesion — and turning them into concrete policies and management tools. This may sound idealistic, but it is, in fact, highly pragmatic. For the first time in human history, technology has disconnected where we live from where we work. Cities are now competing not just on infrastructure or cost, but on quality of life, social connections, environmental conditions, and opportunities for learning and creativity.

I believe the cities of the future will not be mega-cities, but cities of care: human-scale places that combine strong environmental standards, vibrant public space, social life, culture, and knowledge. In that sense, Common Ground is an invitation to reimagine the city as a laboratory of social and economic transformation, where growth is understood not as accumulation, but as care. And Larnaka is an ideal place to test these ideas and prototypes.

4. European Capitals of Culture are often framed as cultural projects, but they’re also economic bets. In your view, what kind of transformation, in jobs, investment, and new businesses, can culture realistically unlock for Larnaka by 2030 and beyond?

European Capitals of Culture are not only cultural programmes. They are powerful economic accelerators, particularly for small and medium-sized cities like Larnaka. By 2030 and beyond, we expect culture to unlock growth primarily through the creative economy, education, and quality-of-life-driven sectors.

We anticipate new jobs and investment in the creative industries, design, especially social and circular design, education, and new technologies. Interest from higher-education institutions is already emerging, while Larnaka’s positioning as a gateway between Europe, the Middle East, and the Arab world strengthens its attractiveness for international collaboration and investment.

Beyond construction, we expect growth in sectors linked to wellbeing, care services for families and older people, and forms of regenerative, year-round tourism that prioritise quality over volume. Importantly, European Capitals of Culture often generate unexpected economic outcomes. Glasgow, for example, attracted call-centre investment after its ECoC year due to improved language and communication skills developed through cultural training, an impact no one initially planned for.

That is the real economic value of culture: it builds skills, confidence, and ecosystems that allow new businesses and opportunities — including ones we cannot yet foresee — to emerge organically.

5. The €30 million Art and Design Centre and the Museum of People are described as the “heart” of the bid and part of a wider regeneration of the former refinery zone. How do you avoid building merely based on an aesthetic and instead make it a real engine for the surrounding neighbourhoods and economy?

From the very beginning, the Art and Design Centre and the Museum of People were conceived not just as iconic buildings, but most importantly, as a living civic infrastructure. Its purpose is not simply to host cultural events, but to function as an everyday meeting place for people of all ages and backgrounds.

Designed by Foster & Partners, the complex prioritises openness, flexibility, and daily use. The spaces are deliberately versatile, allowing a diverse range of activities, from conferences and workshops to performances, exhibitions, and informal social gatherings, to coexist within the same venues. The goal is to make the centre part of daily life, not a destination visited only on special occasions. Operating year-round, from morning to late evening, the centre will host a dense programme of cultural, educational, and design-related activity, while also offering simple reasons to be there: to meet, learn, work, eat, shop, or spend time in a public space.

This constant presence is what turns architecture into an economic and social engine. By generating daily footfall, mixed uses, and long dwell times, the centre can stimulate surrounding businesses, attract complementary services, and support the wider regeneration of the former refinery zone. In that sense, its value lies not in aesthetics alone, but in its ability to anchor a new, active neighbourhood and a more resilient urban economy.

6. The Design Centre is meant to bring together traditional crafts with contemporary design and technologies. What does a successful creative business pipeline look like in this case?

Larnaka has an exceptionally rich base of traditional knowledge and material resources, from lace-making, ceramics, embroidery, bread-making, and jewellery, to agricultural products, salt, seaweed, and other natural materials. These are not nostalgic assets; they are underused economic resources. When combined with contemporary design, research, and new technologies, they can form the basis of a new creative economy.

A successful creative business pipeline starts with this connection. Traditional techniques, for example, embroidery or weaving, can be reinterpreted through contemporary design and become highly attractive to international fashion and design markets that are constantly searching for quality, authenticity, and distinctive production methods.

We have already seen how local tradition can scale globally. The bread-making culture of Athienou, for instance, became the foundation for Zorpas, which now operates internationally. Similar opportunities exist today in areas such as sustainable food, plant-based products, and materials with a lower environmental footprint, sectors that are growing rapidly worldwide.

The Design Centre’s role is to act as an incubator that connects these local resources with designers, researchers, technologists, and tools such as digital fabrication and 3D printing. By supporting experimentation, prototyping, mentoring, and market access, the Centre helps ideas evolve into viable products and, ultimately, into new businesses rooted in place but oriented towards global markets.

7. Larnaka 2030 has already piloted projects like Mahalart, the Larnaka Biodesign Festival, and the Care Festival. What have these early experiments taught you about what people in Larnaka actually want from culture?

These early projects, including Mahalart, Larnaka Biodesign Festival, and Care Festival, taught us something fundamental: culture is most meaningful when it is participatory, not top-down. Art creates real impact not when it is produced for people, but with them.

One moment during the jury visit captured this perfectly. In the refugee housing estate of Agioi Anargyroi, residents shared personal stories of displacement and everyday life. What followed was not a performance, but a shared experience: sitting together in a small living room, drinking coffee, talking, listening. That was culture in its most powerful form: creating common ground through encounter.

From these experiences, we learned to invest in inclusive artistic practices that reach beyond traditional art audiences and that give ownership to diverse communities, especially those whose voices are less visible in public life. People in Larnaka do not want to be passive recipients of culture; they want to be seen, heard, and involved as co-creators.

This is the approach we are scaling through Larnaka 2030. We call it the art of sociability: a cultural practice that builds social skills, trust, and understanding, and strengthens the social fabric of the city in the process.

8. You’re working at the intersection of art, urban development, and technology. Where do you see digital tools genuinely enriching artistic and civic life in Larnaka, and where do you draw the line so that technology doesn’t flatten everything into content?

Digital tools can genuinely enrich artistic and civic life when they extend access, deepen participation, and support collaboration, not when they replace physical presence or human interaction. In Larnaka, technology can help connect people to culture across neighbourhoods, generations, and abilities; support co-creation; and make knowledge, archives, and processes more open and accessible.

We also see real potential in using digital tools to support design, research, and experimentation. For example, through digital fabrication, data-informed urban planning, and hybrid cultural formats that link local experience with international networks. Used well, technology can strengthen the city’s creative capacity and civic intelligence.

When technology turns culture into permanent content and reduces experience to consumption, it stops adding value. Larnaka 2030 prioritises embodied, shared, and place-based experiences.

Technology should amplify care, creativity, and connection, not replace them.

9. For many artists, AI and new media bring both opportunity and fear. As a curator and cultural manager, what do you think the role of the artist is in this moment, and how can a project like Larnaka 2030 protect and amplify that role?

Technological change has always challenged artists, and history shows that artists are never replaced by technology. What changes is the medium, not the human impulse to create, interpret, and make meaning. When cinema emerged, theatre did not disappear; audiences multiplied, and artistic forms expanded. I believe AI will follow a similar path.

Moments like this force us to rethink the essence of art and the role of the artist. If art is treated as decoration or entertainment alone, it is indeed vulnerable. But if art is understood as an essential social function — a way to reflect, imagine, question, and practice citizenship — then it cannot be replaced by machines. Culture is not a sector next to the economy, politics, or technology; it runs horizontally through all of them.

What will change is how art is produced, delivered, and experienced. Artists will increasingly move beyond institutions and events, engaging directly with communities, workplaces, and everyday life. Their role will be less about presentation and more about mediation, helping societies understand themselves during periods of rapid change.

A project like Larnaka 2030 can protect and amplify this role by giving artists time, space, and fair conditions to experiment by embedding artists in neighbourhoods, organisations, and social processes, and by treating them not as content producers, but as critical partners in shaping the future of the city.

10. Do you see Larnaka 2030 as a chance to prototype new models around rights, fair pay, and authorship in the cultural sector, especially as more work goes digital? If so, what practices are you keen to test?

Larnaka 2030 is very much a chance to prototype new models around rights, fair pay, and authorship in the cultural sector. But our starting point is not technology alone; it is the position of artists within society and everyday life.

Today, every neighbourhood has a church and a priest, a permanent, paid figure whose role is not to entertain, but to listen, mediate, bring people together, and accompany communities through everyday life and moments of transition. We are asking: what would it mean to have a similar, stable role for artists? Can we imagine artists or artistic collectives working long-term within neighbourhoods — properly contracted and fairly paid — engaging with different age groups, listening to stories, working through conflicts, aspirations, and shared experiences, and transforming these into artistic processes and public expressions?

We are also exploring similar embedded roles within private companies and organisations, where artists work alongside employees to help teams reflect, collaborate, and articulate their realities through artistic means.

In this sense, Larnaka 2030 is about shifting artists from short-term project providers to recognised social actors. Authorship becomes shared, labour is clearly valued, and artistic work is protected through stable frameworks, not because artists replace existing roles, but because they offer a different, essential form of mediation and meaning-making in contemporary society.

11. Many of our readers are business leaders and founders who still see culture as “soft” compared with infrastructure or finance. What would you tell them about why investing in culture, financially or with their time and networks, is a strategic move, not a “nice-to-have”?

Culture is often described as “soft” because its value is not always immediately measurable. In reality, it is one of the hardest strategic assets a city or an economy can build. Culture shapes skills, behaviours, trust, and identity. These are the foundations of innovation, resilience, and long-term competitiveness.

For business leaders, investing in culture is not philanthropy; it is ecosystem building. Cultural investment develops creative thinking, collaboration, communication, and adaptability, precisely the capabilities companies need in a fast-changing economy. It also directly affects quality of life, which is a key factor in attracting and retaining talent.

Cities that take culture seriously consistently outperform others in attracting people, ideas, and capital. Infrastructure enables movement and transactions; culture enables meaning, belonging, and long-term commitment.

This is why we actively invite business leaders and Forbes readers to engage with Larnaka 2030 — not only as sponsors, but as partners. To connect with our programme, contribute expertise, open networks, and co-create projects at the intersection of culture, business, and society. I am confident they will be surprised by the outcomes — and rewarded by the value created, both economically and socially. Investing in culture is not a “nice-to-have”; it is a strategic choice about the kind of city and economy we want to build for the future.

12. Every European Capital of Culture talks about “legacy”. What will tell you, in 2040, that Larnaka 2030 was more than a one-year festival – that it genuinely changed how people live in and relate to the city?

By 2040, the legacy of Larnaka 2030 will not be measured by events remembered, but by behaviours that have become normal. We will know it succeeded if culture is no longer seen as a separate sector, but as an integral part of how the city plans, educates, cares, and makes decisions.

Concretely, success will mean that cultural spaces are used daily, neighbourhoods continue to co-create projects, and collaboration between citizens, institutions, and businesses has become routine rather than exceptional. It will mean that creative skills, care, and participation are embedded in education, public services, and the local economy.

We will also know it worked if Larnaka remains a city people actively choose, not only to visit, but to live in, because it offers quality of life, social connection, environmental responsibility, and opportunities to create and contribute.

Ultimately, Larnaka 2030 will have succeeded if it changed the city’s operating system: from short-term projects to long-term trust, from consumption to participation, and from growth as accumulation to growth as care.