People with disabilities are the world’s largest minority, around 1.3 billion people, or one in six. As the population ages, the number of people over the age of sixty-five will more than double to 1.6 billion by 2050. Meanwhile, governments and markets are mobilizing trillions of dollars for climate and infrastructure, yet accessibility sits mostly outside the conversation of future-proofing our cities.

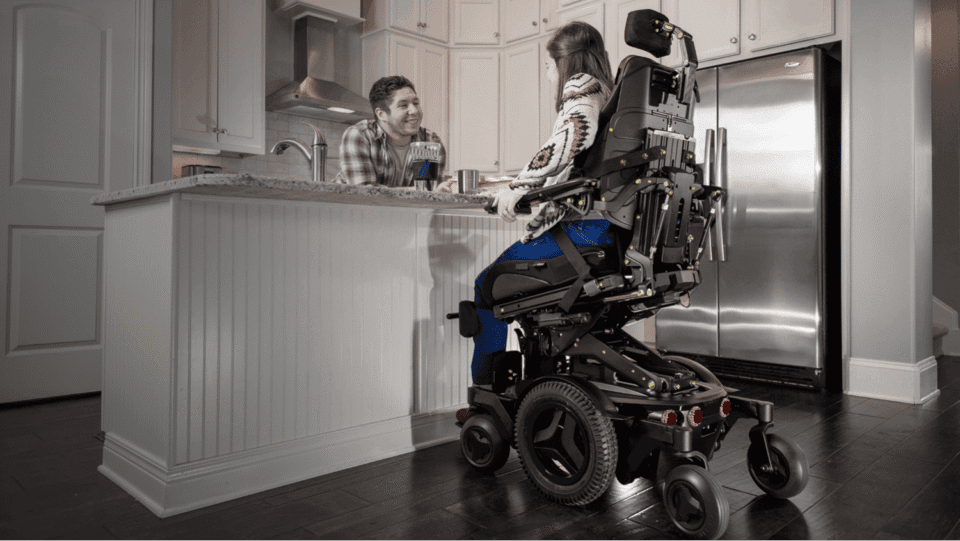

For the 80 million people who need a wheelchair, the world built to standing height still keeps life a few inches out of reach. Traditional wheelchairs solve movement, but they don’t solve presence. You can get into the room, but you can’t get into the conversation at eye level. You can reach the counter, but not the exchange. And because the device locks you into one posture, you’re constantly adjusting to a world that will never adjust back. The problem isn’t the building. It’s the chair.

Follow THE FUTURE on LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, X and Telegram

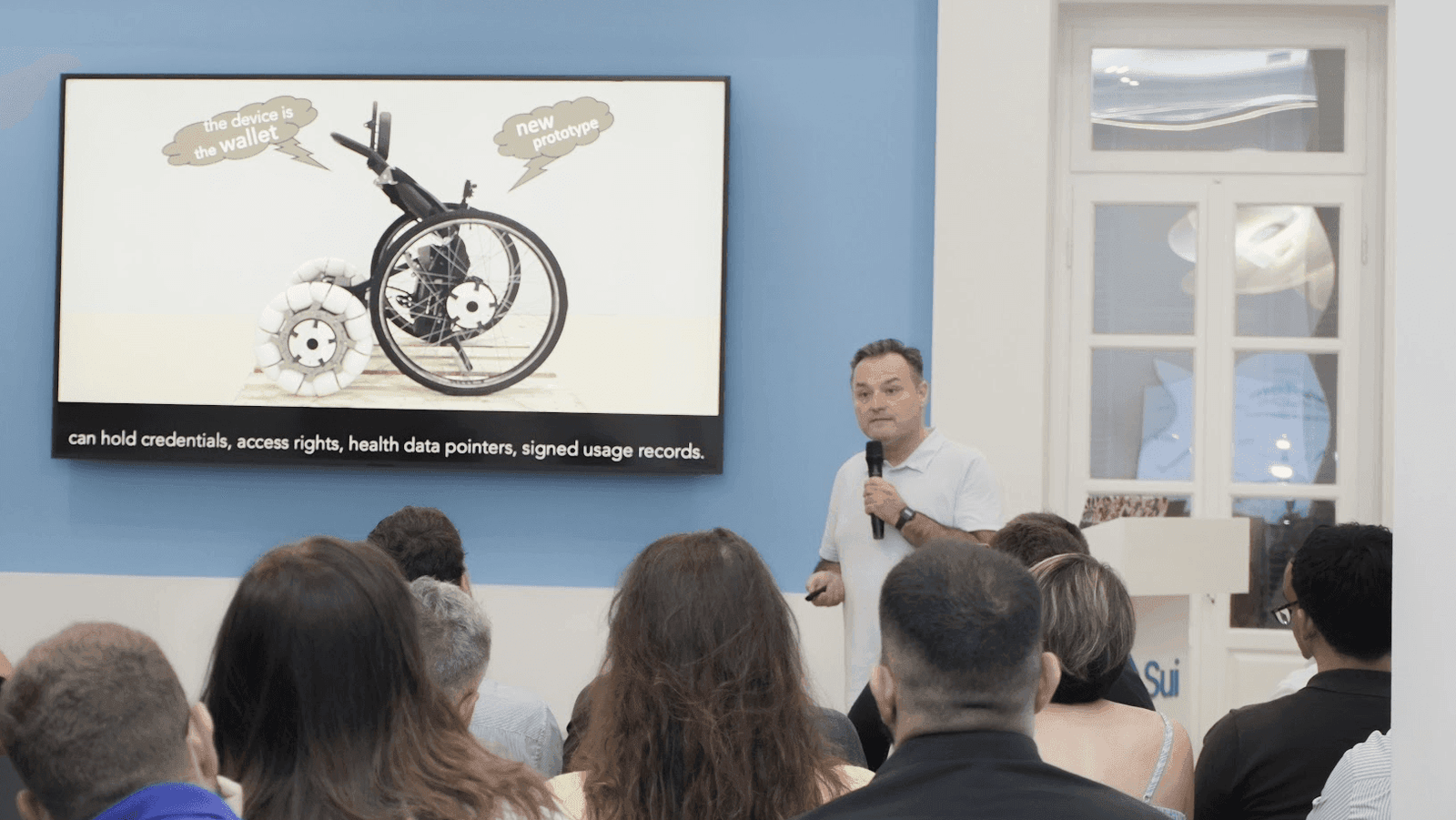

Laddroller is rethinking the device itself. The Greece-based startup has built an intelligent mobility platform that transitions between sitting and standing, fuses telemetry with biometric and environmental sensing, and acts as an active partner rather than a passive tool. By embedding ADAS-style driver assistance, predictive maintenance, and blockchain-secured data ownership, Laddroller transforms the wheelchair from a static constraint into an adaptive platform, one that meets users where they are and lifts them into the spaces where life actually happens.

In this interview with The Future Media, co-founder and CEO Dimitris Petrotos explains how designing buildings revealed the limits of fixed-height mobility, why three layers of sensing make the device intelligent enough to anticipate needs, and what it means to turn users into owners of their own mobility data in a decentralized infrastructure network.

To begin with, what first drew you to Architecture, and how did that interest turn into a drive to design for people who face mobility barriers?

Architecture was my first true passion. It sits at the intersection of art, engineering, and human behavior. When I studied in Florence, I learned that Architecture is not just about shaping buildings, but about shaping experiences. You turn houses into homes; create flows of movement, moments of interaction, and even emotions through materials, light, and structure. But over the years, I began to notice a paradox in the sector: while buildings can be designed to be inclusive, they still fail when the tools people use to navigate them are limited. That was the turning point for me. I began to appreciate how spaces are not just static containers. They influence how people move, how they communicate, and even how they feel about themselves.

When did you first notice everyday barriers that standard wheelchairs do not solve, and what made you decide that the solution had to be a product rather than a renovation?

The truth is, barriers are everywhere. They are so ubiquitous that they almost disappear from public consciousness. Most often, they are the invisible inconveniences that only those bothered by them notice. They all reveal the same pattern: people in traditional wheelchairs are constantly adjusting to a world that refuses to adjust to them. One of the most striking examples is social interaction. Imagine sitting at a table where everyone else is standing. You are literally left out of the conversation because the human brain unconsciously excludes voices from below. That’s not just physical exclusion, that’s psychological marginalization.

My initial question was whether architecture could solve the problem. At first, I thought the answer lay in architectural retrofits: wider elevators, adjustable-height counters, different layouts perhaps. But I quickly realized this would be a never-ending battle, and, at best, it would only chip away at the problem. The common denominator was not the environment; it was the device. A chair that cannot stand, cannot adapt, cannot connect is a chair that excludes. That’s why the solution had to be a product; not another renovation project or accessibility feature bolted onto a building, but a complete rethinking of personal mobility itself.

How would you describe what Laddroller is?

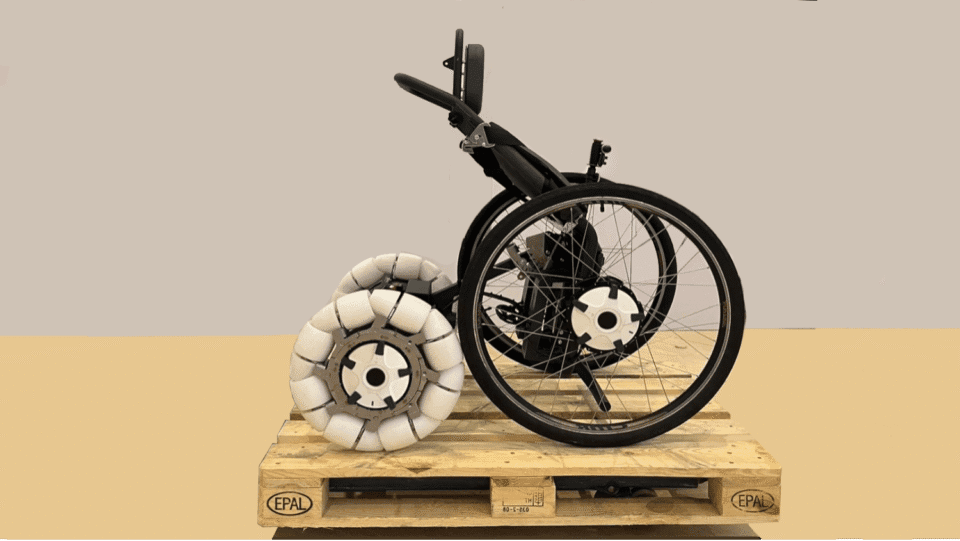

Laddroller is not just a wheelchair. It is a new species of mobility. An intelligent mobility platform for the connected era. It is designed around three distinct layers of sensing and intelligence that create a holistic picture of the user and their environment.

At its heart, Laddroller is built on three distinct but complementary sensor layers. The first layer is telemetry, which monitors the machine itself: torque sensors in the hub motors, gyroscopic balance readings, and battery health diagnostics. This ensures the device knows its own state at all times. The second layer is biometric, which focuses on the user: posture sensors, heart rate variability trackers, muscle stress monitors, and even skin temperature. This allows the device to sense fatigue, discomfort, or stress before the user articulates it. The third layer is environmental, which maps the external world: lidar arrays, ultrasonic pings, AI-vision cameras that recognize obstacles, surfaces, signage, and even crowd flow in real-time.

These three layers fuse into a constantly updated digital twin, not just of the device but of the person and their environment together. These layers create what we call a “connected exosystem.” The device doesn’t just respond to commands; it anticipates needs. It knows when to shift you into standing mode so you can converse naturally. It knows when to slow down because a cat just darted across the corridor. It knows when to recommend a break because your vitals show fatigue, or when it’s time to recharge itself. It’s connected not only to the user but to the city itself, feeding into smart infrastructure and creating the backbone for a decentralized physical infrastructure network (DePIN). In short, Laddroller is a shape-shifting, data-secure, autonomous partner for daily life.

Who is on your core team today?

Our team loves building things that people all over the world use. We are fortunate that we are paid to do what we love. On top of that, the whole team mirrors the interdisciplinarity of the product. I bring the background of architecture, IoT, and distributed ledger technologies, combined with an inventor’s instinct honed through recognition at ETH Zurich in Europe, MIT in the US, and Tsinghua in China, just to name a few. My role has always been to ask all the uncomfortable questions, but also to simplify the complex and hire the best.

My co-founder and Chief Scientist, Vassiliki-Georgia, is a physicist with a medical school PhD in Biophysics, who has mastered the language of biomimicry. She studies how bird skeletons balance strength and lightness, or how bamboo distributes stress, and she brings that wisdom into the mechanical design of the device. That’s why Laddroller can change shape fluidly without sacrificing robustness.

Then there’s Giorgos and Aharon, our lead software engineers. They are the ones who ensure that the three layers of sensors speak the same language. They build the AI that makes autonomous navigation possible, stitching together input from lidar, ultrasonic, and vision systems into one seamless stream. Without their work, the “intelligence” of our smart mobility device would remain just a cool idea.

What driver assistance features are you building into Laddroller?

Driver assistance in Laddroller is built like an ADAS suite for cars, but scaled to human mobility. The same principles that revolutionized automotive safety are now entering the world of personal devices. Features include adaptive speed control that adjusts based on terrain and crowd density, lane assistance in environments like airports, predictive obstacle avoidance powered by multi-sensor fusion, and emergency auto-braking.

One of our most exciting features is autonomous repositioning: the device can gently reposition itself in a queue or circle back to the user if they briefly step away, like for example, when they are taking a nap. Obstacle avoidance is handled through a fusion of ultrasonic, infrared, and lidar. The device doesn’t just detect objects; it interprets them. It knows the difference between a static obstacle like a bench, something temporary like a stroller, or a dynamic obstacle like a person walking. Predictive braking ensures safety by anticipating collisions milliseconds before they occur.

But we go beyond safety. We’re introducing “follow-me” mode, where the device autonomously follows a companion or caregiver. We’re developing “point-to-point navigation,” where the user can set a destination in a mapped building and let the device find the best route. And because of our biometric sensors, we can tie driving assistance to the user’s condition: if vitals show fatigue, the device increases autonomy; if the user feels alert, it returns control.

We are also integrating geo-fenced navigation for commercial spaces. In a mall, for example, a user can select “elevator” on their screen and Laddroller will autonomously take them there, communicating with IoT-enabled infrastructure as it moves. This is not science fiction; it’s a logical extension of the sensor layers already embedded in the device.

The future is not just about wheels that move, but wheels that think. It’s about building a continuum between user control and machine assistance, where dignity is always preserved and safety is never compromised.

How does onboard telemetry help with maintenance and clinical follow-up?

Telemetry transforms both maintenance and healthcare. From a maintenance perspective, this means predictive servicing rather than reactive repair. Torque sensors in the hub motors, for example, can detect subtle inefficiencies long before they become audible or visible. Changes in battery discharge curves can indicate when cells are losing capacity, enabling replacement before failure. The device immediately sends us an update of its state of health in real time, so downtime is minimized. This allows predictive maintenance rather than reactive fixes, reducing downtime. Traditionally, wheelchairs have always been black boxes; you know something is wrong only when it breaks down, and clinical follow-up is based on self-reporting, which is subjective and limited. With Laddroller, every mechanical, biometric, and environmental interaction is captured in structured data.

From a clinical perspective, telemetry is even more powerful. A breakthrough, really. We can monitor how often a user transitions from sitting to standing, how long they sustain that posture, whether their posture is optimal, whether they lean or compensate asymmetrically, and how their cardiovascular system responds. This provides objective data to supplement clinical observations, making rehabilitation programs more precise. Through a remote secure dashboard, a physiotherapist can review a month of usage data and adjust therapy plans accordingly. They see not just snapshots from a clinic visit but a continuous record of daily life. This transforms rehabilitation from episodic to continuous. It also generates longitudinal datasets that can inform broader research into disability, mobility, and human-machine interaction.

In essence, telemetry closes the feedback loop: the device takes care of itself, while also empowering clinicians to take better care of the user. This is how Laddroller evolves from a mobility device into a health partner.

How is sensitive user data stored on the device, and who controls access?

All sensitive data, biometric readings, usage patterns, and environmental interactions are stored locally on encrypted solid-state modules inside the controllers of the device itself and never on third-party servers by design. This is critical: the data never defaults to a cloud controlled by us or by a third party. Instead, the user owns it, literally. The architecture is closer to a crypto hardware wallet than to a traditional medical record system.

Access permissions can be granted through blockchain-based smart contracts, which means sharing is always transparent and revocable. If a user wants to share a week’s worth of posture data with their physiotherapist, they issue a revocable permission that specifies exactly what data, for how long, and for what purpose. If they want to revoke it, it disappears instantly. Nothing is ever beyond their control.

This approach flips the script. Instead of patients becoming sources of exploitable data, they become sovereign nodes in a secure network. In effect, Laddroller doubles as a hardware crypto wallet, with the same security principles that protect billions of dollars in digital assets. No medical record leaves the device without explicit, cryptographically signed consent.

In a world where medical data leaks and ransomware attacks are tragically common, this isn’t just a technical feature; it’s a promise of dignity and control.

Let’s talk more about the blockchain components you are using in the design of Ladroller.

Blockchain is not decorative here; it is functional, it is part of its nervous system. We see Laddroller as a node in a DePIN (Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Network), where physical devices interact through secure, transparent protocols. Every data point, from mechanical diagnostics to anonymized movement patterns, can be immutably stored on-chain. Blockchain ensures that all data, telemetry, biometrics, and environmental mapping are recorded immutably, with user ownership intact. For users, this enables control and, more importantly, it enables data monetization as a form of empowerment. Imagine urban planners in Singapore or Manila wanting to understand traffic flow data, or a research consortium in Manila might want to obtain anonymized real-world biometric usage data. Using our tech, they will be able to purchase anonymized mobility and biometric data directly from users, with payments streamed securely. Users, for the first time, can derive value from their lived experience instead of giving it away.

Blockchain also allows seamless integration with insurers, hospitals, or rehabilitation networks. For example, a clinician can confirm that standing sessions meet a prescribed therapy threshold, not by trusting reports, but by verifying signed blockchain records. This removes friction and builds trust between the patient, provider, and payer.

So for users, blockchain means three things: sovereignty, dignity, and opportunity. It transforms mobility data from a vulnerability into a personal asset.

The user decides what to share, and because blockchain governs the transaction, the data cannot be tampered with. In this way, mobility becomes not just physical freedom, but digital empowerment.

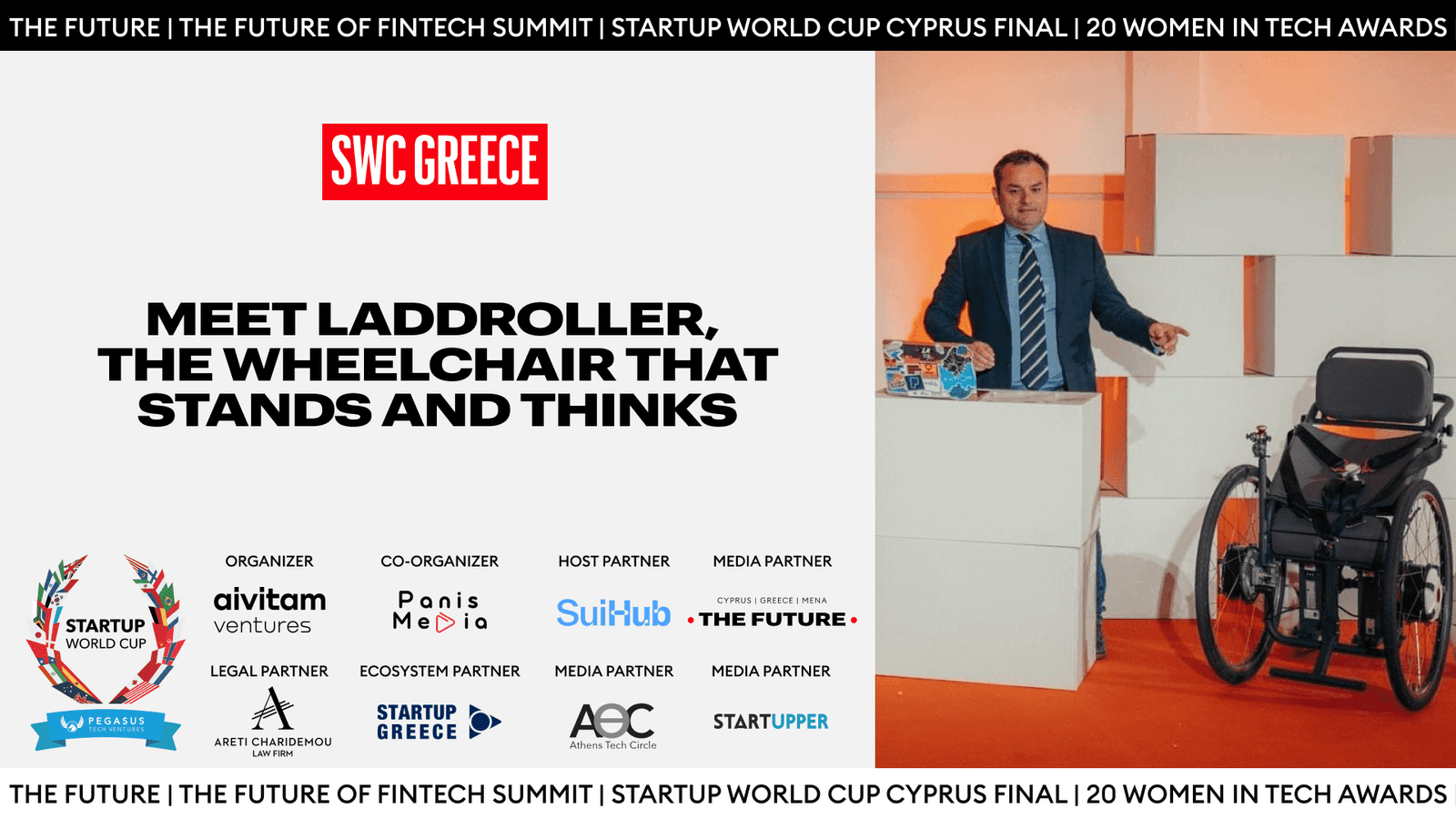

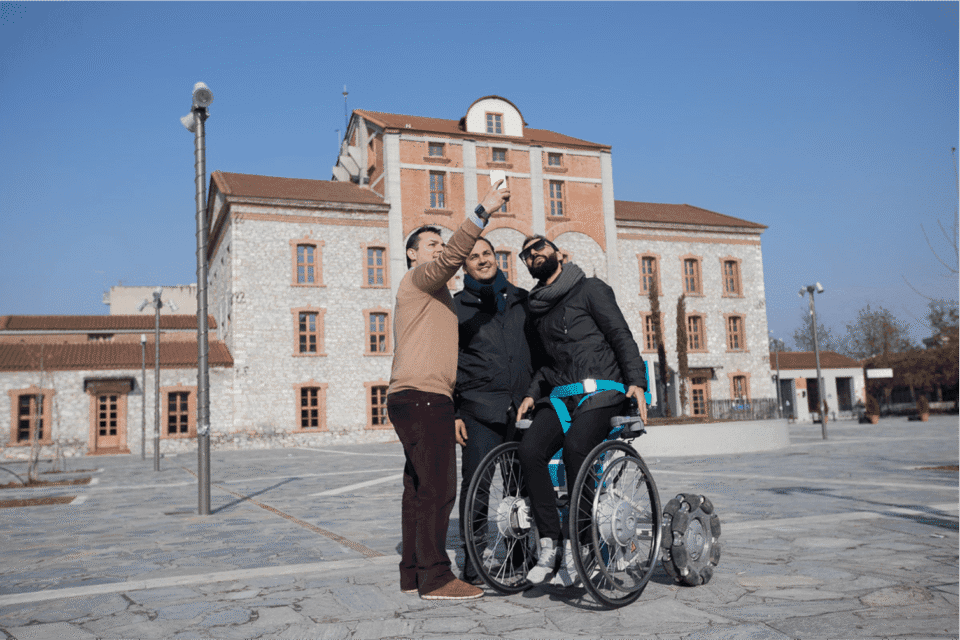

Why did you step onto the Startup World Cup Greece stage, and what did you take away from it?

We went to the Startup World Cup Greece not just to pitch our tech, but to pressure-test our vision. When you step onto that stage, you’re exposing your ideas to some of the sharpest minds in innovation, investment, and technology. For us, it was about validation and visibility.

The experience was electric. We were surrounded by startups working on AI, green energy, and space tech. To stand among them and say, “We are reinventing mobility for dignity and inclusion,” was powerful. What we took away was confirmation that our idea resonated far beyond assistive technology. Investors and observers saw it as healthcare, as robotics, as IoT, as blockchain, as urban mobility. That multidimensionality is our strength.

When we received the Audience Favorite Award, it wasn’t just applause for a cool piece of hardware. It was a recognition of a deeper mission. That moment told us we’re not just building a product; we’re building a movement. It was validation that the world is ready for a mobility revolution grounded in empathy, intelligence, and design.

Looking ahead, what does success over the next two years look like for Laddroller?

Success is multidimensional. First, it means scaling production. Today, we are at the prototype and pilot stage. In two years, we aim to manufacture at scale, moving from dozens of units to thousands, with factories equipped to assemble devices for both healthcare and retail markets.

Second, success means regulatory validation. FDA approval in the US, CE marking in Europe, and strong partnerships in Asia will be critical. These are not just bureaucratic milestones; they are gateways to trust and adoption.

Third, success means social impact. I envision fleets of Laddrollers in shopping malls, airports, hospitals, and city centers. Not just as mobility aids, but as connected urban devices, interacting with IoT systems, integrating with smart infrastructure, generating valuable data streams, and securing those streams with blockchain.

And most importantly, success is human. It means that thousands of people who once lived with constant compromise will now live with dignity, autonomy, and inclusion. When I see a user navigating a store aisle in standing position, chatting eye-to-eye with a friend, while their device is simultaneously securing their data and predicting their next move, I’ll know we’ve succeeded.