A film incentive—also known as a rebate or tax credit—is a government-supported program that returns a portion of qualified local production spending to filmmakers. These incentives are designed to attract international productions, build local industry capacity, and boost exclusive tourism appeal via global media exposure.

Since 2017, the number of regions offering such schemes has surged by 39%, according to Olsberg SPI’s 2024 report. Even amid a 20% drop in global film and TV production in the second quarter of 2024, countries with “dependable” incentive systems, such as Canada and the UK, along with Ireland, which now offers a bankable incentive of 40%, continued to secure international production investment. Analysts at Kearney describe these incentives as “indispensable” for transforming local film cultures into “global media hubs,” citing their impact on GDP, job creation, tourism, and, potentially, political diplomacy.

Follow THE FUTURE on LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, X and Telegram

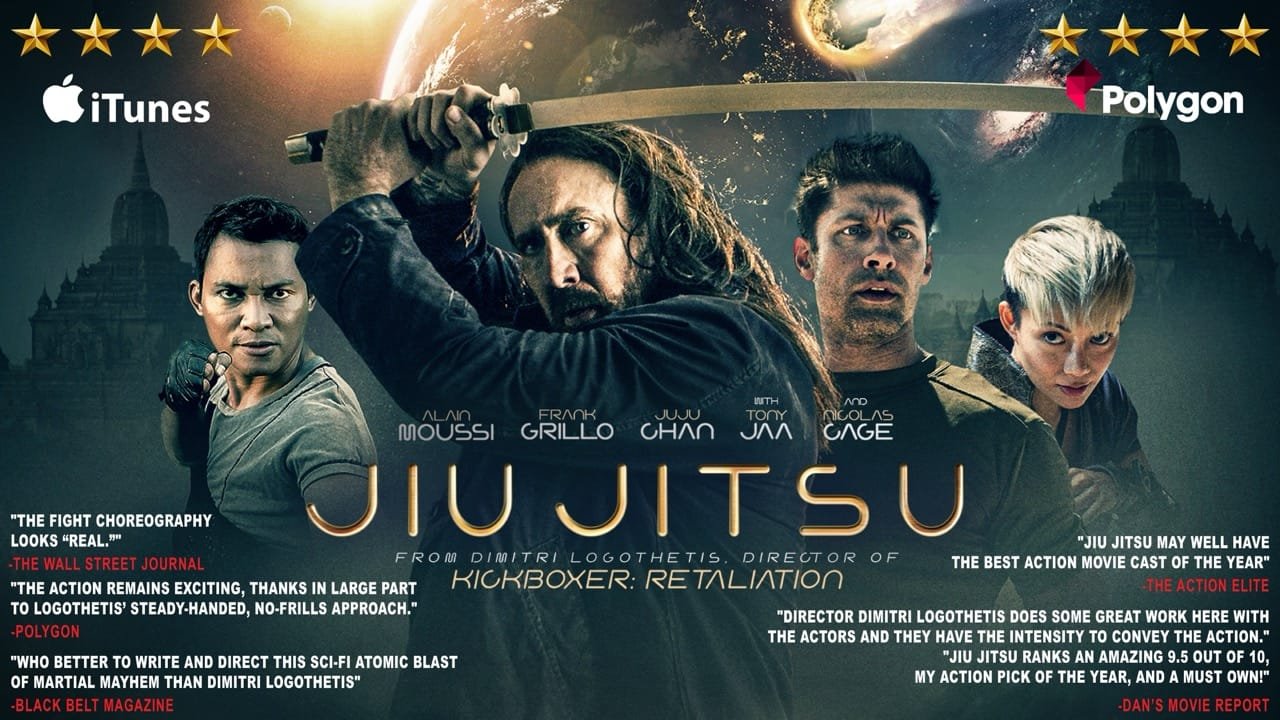

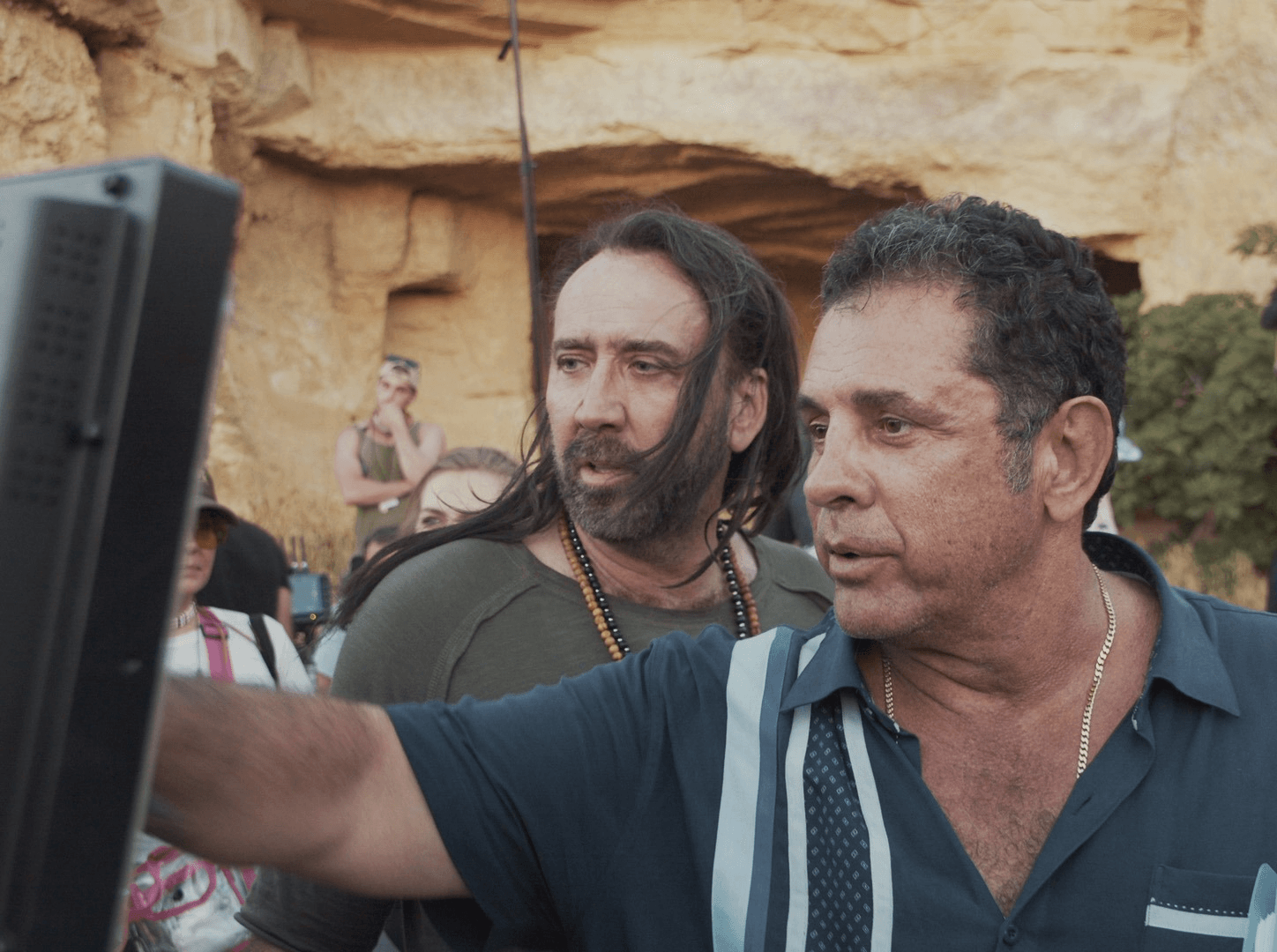

In 2019, Cyprus introduced its “Olivewood” incentive, offering up to 40% back on qualifying local production spend. Director Dimitri Logothetis was among the first to test the scheme, bringing his EU 20 million sci-fi action film Jiu Jitsu, starring Nicholas Cage, to the island.

In an exclusive interview with The Future Media, he recalls flying in, along with 50 or so other producers from around the world, for a Cyprus Invest Film symposium, with ministers about the newly-launched rebate scheme:

“We met the Minister of Finance and the de facto film commissioner, Lefteris Elefteriou, and they took us on tour of the island […] And I thought that it would be a really good opportunity to be able to shoot in the country, especially one, being a Greek born American, that I felt connected to […] the landscape and the fact that it’s sunny most of the time […] And the rebate program was robust at the time.”

But despite the early promise, the Olivewood scheme failed to meet the most critical test of a successful Incentive program: delivering payouts on time, or for the Jiu Jitsu investors, “paying anything at all to this day.”

The result was a loss of industry trust and a pause in the momentum for Cyprus’s aspirations to establish itself as a serious contender in the film incentive arena.

Incentive Success Stories: Lessons from Malta, Greece & the UK

Cyprus isn’t the first country to offer its landscapes as the backdrop for international film production, and it certainly won’t be the last. But as global examples show, success in this space goes beyond offering a rebate. It requires building credibility and trust, maintaining a reputation for consistency and reliability, and investing in the infrastructure needed to support large-scale international productions.

Malta

Malta, with a population of roughly 500,000, launched its rebate program in 2006, with significant enhancements in 2014 and 2019. Today, the country offers up to a 40% cash rebate on qualifying local spend. Productions must spend at least €100,000 locally, with budgets exceeding €200,000.

Since the introduction of the 40% incentive, annual film production spend rose from €40 million in 2019 to around €85 million by 2022. In 2022, films and TV productions contributed €72.7 million in local expenditure, generating €93.8 million in gross value added, roughly a 3:1 return, i.e., every €1 rebated produced €3 in economic returns. According to government data, these incentives supported 1,772 full-time relevant jobs in 2022, 78% of which were filled by Maltese crew and talent. Beyond the direct spend and job creation, film production generates a measurable trickle-down effect across the local economy. A single feature or TV series requires set construction, equipment rentals, transport services, catering, and accommodation, creating demand for local vendors and businesses. The result is not just job creation. In Malta, this activity contributed to a measurable increase in national GDP alongside global media coverage. For an economy that relies significantly on tourism, this type of free international advertising was invaluable.

Major titles such as Gladiator (1999), Troy (2004), Munich (2005), Captain Phillips (2013), Assassin’s Creed (2016), and Game of Thrones (2011) have all filmed scenes at Malta’s historic forts and studios. Most recently, Gladiator II returned to shoot at Fort Ricasoli, a 17th-century bastioned fortress built by the Knights of St. John, bringing the largest rebate ever issued by an EU country (€46.7 million) and recreating ancient Rome on Maltese soil.

Greece

Greece has steadily built its cash rebate framework since 2017, when it introduced a 25% rebate under Law 4487/2017. In 2018, this was raised to 35%, and then to a full 40% in 2020, expanding eligibility to include foreign crew salaries. This competitive move positioned Greece on par with leaders like Ireland and Hungary.

By late 2023:

- 393 productions had been approved

- €795 million had been invested locally

- €105 million in rebates had been disbursed

- €50 million was paid out in 2023 alone

Greece’s Prime Minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, has expressed strong support for local filmmaking and considers it a priority.

Research by the Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (ΙΟΒΕ) suggests that a typical €20 million production in Greece generates approximately €39 million in GDP and supports around 750 jobs. Productions such as Glass Onion (2022), Knives Out, The Lost Daughter (2021), and Disney’s Crater have all taken advantage of the rebate, showcasing Greek islands and urban centers to global audiences. Tourism boosts have followed, especially in Corfu and Spetses, where new data from the Greek Tourism Confederation shows a notable increase in off-season bookings following major film releases.

United Kingdom

The UK’s Film Tax Relief program, launched in 2007 and significantly expanded in 2015, offers a 25% cash rebate on qualifying production spending, with an additional 15% for independent films under £15 million. As of 2024, this program evolved into the AudioVisual Expenditure Credit (AVEC), maintaining generous net rates:

- 25.5% for live-action features

- 29.25% for animation and high-end TV

- 39.75% for eligible independent features under £15 million.

By 2024, the UK saw £5.6 billion in film and high-end TV production spend, up 31% increase over 2023. HMRC estimates annual relief payouts will reach £640 million by 2024–25. A 2019 study revealed that for every £1 rebated generated £8.30 in gross economic value.

Major productions like Dune: Part Two, No Time To Die, Star Wars, and Jurassic World Dominion have used UK studios for their productions. Disney alone claimed £1.6 billion in UK tax credits over 15 years, supporting more than 50 movies and TV shows, and generating over £10.6 billion in local spend.

Together, these incentives place the UK’s reputation as a top-tier destination for international production.

Olivewood in Context

Cyprus introduced its “Olivewood” rebate scheme back in September 2017 (Cabinet Decision 83.415), updating it in 2019 and again in 2020 to boost its appeal. The scheme runs under the EU State Aid through December 31, 2026, with a budget cap of €25 million per year.

In practical terms, the scheme promised one of Europe’s highest incentives:

- Broad eligibility covered feature films, TV series, animation, documentaries, even reality and natural history series.

- Up to 40% cash rebate on eligible Cyprus expenditures, 40% for “below-the-line” costs, and 25% for “above-the-line,” all determined through a cultural scoring system.

- Producers could also opt for a tax credit alternative, offsetting up to 50% of taxable income.

- Additional benefits included VAT refunds and infrastructure tax deductions (20% for small enterprises, 10% for medium).

- Feature films must spend a minimum of €200,000 in Cyprus; TV drama series require €100,000, and documentaries €50,000.

- Productions were required to spend at least 20% of their total budget in Cyprus and hire a minimum of one EU/EEA cast member plus a set crew count.

- Critically, rebate payouts were officially due within 90 days of final audit approval.

Overall, Cyprus’s rebate scheme appeared to be financially competitive. It broadly matches regional peers in eligibility, rebate amounts, and add-on incentives.

But as a brand-new entrant to the market, Cyprus was under a magnifying glass. Film financiers, producers, and legal teams around the world watched closely to see whether the island could deliver not just a rebate but a credible, reliable system. In this industry, reputation is everything.

“The very first phone call I make is to my bankers… If [a country] doesn’t have a reputation over the years of paying, then the bankers will say no. And once the bankers say no, then Hollywood says no, then the world says no,” —director-producer Dimitri Logothetis.

That track record built over years of timely payouts, legal clarity, and operational consistency is what gives schemes in places like Malta and the UK their competitive edge. Cyprus had the chance to follow in the footsteps of those “success stories.” Instead, as the first wave of films entered the system, including the €20 million production Jiu Jitsu, rebate payments stalled despite audits conducted by KPMG and confirmed by PWC. As delays stretched into months and then years, film bankers withdrew their confidence, and with them, the potential of future investment.

For a scheme designed to launch Cyprus onto the global filmmaking stage, its debut became a cautionary tale.

Where Olivewood Stumbled: The Jiu Jitsu Case Study

To understand where Cyprus’s film incentive effort fell short, this section draws on the firsthand experience of director-producer Dimitri Logothetis, whose €20 million production Jiu Jitsu was one of the first projects to go through the Olivewood scheme.

1. Audit Clearance

Jiu Jitsu’s producers, working under the Olivewood scheme, say they followed the outlined procedures meticulously. International auditing firm KPMG Cyprus was brought on to manage financial reporting, with findings later reviewed by government-appointed auditors, PwC. According to the production team, full documentation was submitted after the production was completed, with expectations set by the scheme itself: rebate payments were to be issued to Jiu Jitsu’s investment fund, within 90 days of final audit approval.

Despite these efforts, payments did not arrive within that timeframe. The film team described months-long waits with little to no formal communication about the cause. As director-producer Dimitri Logothetis recalled:

“Once you get the 20th or 30th or 40th excuse… you know that they just don’t want to pay. Jiu Jitsu was completed over 5 years ago, and still our investment fund has not been paid one Euro!”

To date, no official explanation has been published by the Cypriot authorities regarding the extended delays. While the COVID crisis, internal government processes, or compliance reviews may have contributed, the lack of clarity from the Cypriot civil servants led to increasing unease.

2. Too Many Committees

In countries with established reputations for film incentives, administration is typically handled by a single, centralized authority, usually a government body with operational independence. These film commissions are tasked with managing applications, verifying eligibility, and ensuring timely disbursements.

Cyprus, by contrast, did not establish a centralized body to manage the Olivewood scheme. Instead, the process depended on getting approvals from various panels, advisory boards, investment committees, and ministerial departments. For producers, this led to prolonged delays, a lack of clarity, confusion, and frustration with little recourse or accountability when issues arose.

Logothetis contrasts this with his experience elsewhere:

“I normally call an experienced film commissioner in a US state or a country around the world. They have a few people on staff and an annual budget. They know me by name, and they know I’m a consistent, high-profile filmmaker, with major Academy Award-winning actors like Morgan Freeman and Nic Cage. The film application is simple and approved by the film commissioner or his or her staff. I take the approved application to my banker, and he will loan against it. Once the film is complete, we have an approved local auditor like KPMG audit the spend. The audit is submitted to the same commissioner who reviews and approves, and the state or country pays the banker back! Period. No committees, no Minister of Finance, just payment back to the bank.”

The absence of a structure undermined trust with partners who depended on reliable and coherent execution.

3. Bank Fallout

The viability of a rebate scheme depends not only on its legal framework but also on its ability to support production financing. In Cyprus, producers entered Olivewood expecting certified rebates—once audits were cleared—to be used as collateral. International banks were prepared to finance projects based on that expectation, provided rebates were delivered on time and the process remained consistent.

In the case of Jiu-Jitsu, payments were delayed for months beyond the 90-day window stated in the scheme. Projects relying on rebate-backed loans were left without financing when banks withdrew support. Some producers were forced to abandon or relocate projects after losing secured capital.

Logothetis describes the contrast between Cyprus and more established markets:

“I met with several Cypriot banks, including Hellenic Bank, Bank of Cyprus, and Astro Bank, who had little to no faith that the Cypriot government would pay the film rebate. It’s the opposite in Canada, the UK, or Ireland. The local banks in these countries trust the local government to pay their debt. I challenge Cyprus Invest to find one bank that will honor their paper and loan against their film rebate!”

Once a scheme fails to meet its financial commitments, its credibility suffers. In this business, reputation matters at the financing level first. Without it, future productions simply go elsewhere.

4. Test Case

When Cyprus introduced Olivewood, it was entering a highly competitive international market. With no prior track record, the first projects were seen as test cases by the rest of the industry. The first few productions were meant to demonstrate Cyprus’s readiness to compete. Instead, delays in payments and a lack of follow-through signaled deeper structural issues.

This had wider consequences. The setback didn’t just cost Cyprus a few productions; it stifled the kind of early momentum that countries like Greece and Malta used to build long-term credibility. As a newcomer in an industry where reputations are worth more than financial incentives, Cyprus had one chance to make a strong first impression. That window has passed—for now.

The Road to Recovery

While Cyprus may have lost ground in the early rollout of its incentive program, recovery is possible, but only with demonstrated commitment, operational reform, and institutional accountability. As other countries have shown, industry trust can be rebuilt, provided there is clarity, accountability, and follow-through. Our conversations with producers, financiers, and legal experts point to three concrete priorities:

1. Resolve Outstanding Rebates

Trust begins with honoring existing commitments. Several production teams, including those behind Jiu Jitsu, are still waiting for the full disbursement of their approved rebates. Delays have created financial losses and reputational damage. Until these obligations are met and met transparently, new entrants will remain skeptical. Cyprus can begin to restore confidence by publicly confirming outstanding payments and communicating clear timelines to the industry.

2. Centralize and Professionalize Administration

Unlike Greece or the UK, which operate their schemes through independent, non-politicized, centralized film bodies, Cyprus still lacks a dedicated film authority with operational independence. Such a Commissioner should be empowered, without government interference to oversee the entire process, enforce timelines, ensure accountability, pay the rebate after the audit on time, and operate independently from political cycles. As one producer put it, “You need one door to knock on, not five.”

3. Reintroduce the Scheme with a Refined, Realistic Pitch

Cyprus doesn’t need to promise the highest rebate. It needs to promise consistency. A relaunch of Olivewood, potentially under a new name or framework, could benefit from the appointment of an experienced, internationally respected Film Commissioner, ideally someone with a proven track record in managing successful incentive programs abroad. The new scheme should emphasize lessons learned, updated processes, and competitive (but realistic) incentives. Complementing the scheme with investment in local talent and co-production pathways would strengthen Cyprus’s role as a production partner, not just a scenic location.

A Legal Battle, Missed Productions, and Gunner

The damage from Cyprus’s handling of Olivewood has now escalated beyond bureaucracy and into court. The producers of Jiu Jitsu, represented by Y. Georgiades & Associates LLC, have filed two ongoing legal actions: one against the Republic of Cyprus and another against the now-impeached Auditor General. They assert they have been denied millions in rebates, along with millions in lost wages, and seek damages for these broken commitments.

Meanwhile, director-producer Dimitri Logothetis has continued to focus on new projects. His latest award-winning film, Gunner, starring Morgan Freeman and Luke Hemsworth, was released by Warner Bros.

In the U.S. and Canada in August 2024. Despite initial considerations to shoot in Cyprus, he ultimately moved production stateside. As Logothetis explained, “We had the beaches, the mountains, the towns—it was perfect. But after what happened with Jiu Jitsu, my investors would think I was a fool to trust the Cypriot politicians again.”

Gunner performed solidly upon release: debuting in the top 10 across all genres on Apple TV U.S., and ranking #3 in the Action & Adventure category. To date, the film has won 18 film festivals worldwide. Logothetis has other projects in development. These include high-concept action films and international co-productions, exactly the type of projects the Olivewood scheme was designed to attract.

Logothetis, who once championed Cyprus’s potential as a filming destination, expressed disappointment not in the local talent but in the system that failed them:

“It’s unfair to the people of Cyprus, who were skilled, creative, and driven in my experience, but it is the reality. It’s a missed opportunity, but I don’t think I will return.”

His lawyer, Yiannos Georgiades, highlighted the broader impact:

“This isn’t just about one film. It’s about the message we send to international investors, studios, and streaming platforms. Right now, that message is: proceed at your own risk. That’s a tragedy for filmmakers, for local crews, and the Cypriot economy.”

Rewriting the Script

Cyprus launched Olivewood with a vision but faltered on execution. When rebates were not paid, litigation followed, and international productions began to walk. It is not just lost film days or cut budgets; it is the loss of trust.

Rebuilding that trust starts with clearing outstanding rebates and acknowledging legal claims. Then comes institutional reform: a unified, independent film authority that operates with industry, bank, and investor confidence. Finally, relaunching with realistic promises and delivering on each one can bring Cyprus back into the Mediterranean, European, and even global film circuit.

Logothetis summed it up best:

“It’s like a credit card. If you don’t pay on time, they cancel the card, and you’re not going to get another one. Reputation is everything.”

Cyprus’s landscapes and talent remain. What’s needed now is credibility and follow-through. The stage is still set; the question is whether the country will deliver the performance.